History of art - Ancient Art

Ancient art

In the first period of recorded history, art coincided with writing. The great civilizations of the Near East: Egypt and Mesopotamia arose. Globally, during this period the first great cities appeared near major rivers: the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, Indus and Yellow Rivers.

One of the great advances of this period was writing, which was developed from the tradition of communication using pictures. The first form of writing were the Jiahu symbols from neolithic China, but the first true writing was cuneiform script, which emerged in Mesopotamia c. 3500 BCE, written on clay tablets. It was based on pictographic and ideographic elements, while later Sumerians developed syllablesfor writing, reflecting the phonology and syntax of the Sumerian language. In Egypt hieroglyphic writing was developed using pictures as well, appearing on art such as the Narmer Palette (3,100 BCE).

Ancient Near East

Mesopotamian art was developed in the area between Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in modern day Syria and Iraq, where since the 4th millennium BCE many different cultures existed such as Sumer, Akkad, Amorite and Chaldea. Mesopotamian architecture was characterized by the use of bricks, lintels, and cone mosaic. Notable are the ziggurats, large temples in the form of step pyramids. The tomb was a chamber covered with a false dome, as in some examples found at Ur. There were also palaces walled with a terrace in the form of a ziggurat, where gardens were an important feature. The Hanging Gardens of Babylonwas one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Relief sculpture was developed in wood and stone. Sculpture depicted religious, military, and hunting scenes, including both human and animal figures. In the Sumerian period, small statues of people were produced. These statues had an angular form and were produced from colored stone. The figures typically had bald head with hands folded on the chest. In the Akkadian period, statues depicted figures with long hair and beards, such as the stele of Naram-Sin. In the Amorite period (or Neosumerian), statues represented kings from Gudea of Lagash, with their mantle and a turban on their heads and their hands on their chests. During Babylonian rule, the stele of Hammurabi was important, as it depicted the great king Hammurabi above a written copy of the laws that he introduced. Assyrian sculpture is notable for its anthropomorphism of cattle and the winged genie, which is depicted flying in many reliefs depicting war and hunting scenes, such as in the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.

Sumerian

Cast of the Warka Vase

Cast of the Warka Vase Diorite Statue I, patesi of Lagash(2120 BCE), Louvre

Diorite Statue I, patesi of Lagash(2120 BCE), Louvre Statue of Ebih-Il, a high priest of the Ishtar (the goddess of love and war), from Mari (Syria), circa 2400 BCE, Louvre

Statue of Ebih-Il, a high priest of the Ishtar (the goddess of love and war), from Mari (Syria), circa 2400 BCE, Louvre Standing male worshiper from the Tell Asmar Hoard

Standing male worshiper from the Tell Asmar Hoard Fragmentary relief dedicated to the goddess Ninsun, mother of Gilgamesh, steatite, circa 2255–2040 BC, (Neo-Sumerian Period), Louvre

Fragmentary relief dedicated to the goddess Ninsun, mother of Gilgamesh, steatite, circa 2255–2040 BC, (Neo-Sumerian Period), Louvre Standard of Ur

Standard of Ur- Two of the Lyres of Ur (the Queen's lyre and the silver lyre, Royal Cemetery at Ur)

Ram in a Thicket, British Museum(London)

Ram in a Thicket, British Museum(London) Royal Game of Ur, British Museum

Royal Game of Ur, British Museum- Reconstructed Sumerian headgear necklaces found in the tomb of Puabi, circa 2500 BC, British Museum. This lavish jewels feture precious stones from Ur's varied trading partners

- Columns with clay mosaic cones from the Eanna precinct in Uruk, dating from 3600-3200 BC. The clay cones were painted in red, black and white and were inserted in such a way that they created geometrical designs on the surface of the columns. The columns are on permanent display at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin (Germany)

The Mask of Warka

The Mask of Warka Sumerian male worshiper, circa 2300 BC, calcite-alabaster, height: 19.5 cm (7.6 in), Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, United States). The shaven head, a sign of ritual purity, may identify this figure as a priest. A partially preserved inscription on one shoulder states that he prays to Ninshubur, the goddess associated with the planet Mercury

Sumerian male worshiper, circa 2300 BC, calcite-alabaster, height: 19.5 cm (7.6 in), Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, United States). The shaven head, a sign of ritual purity, may identify this figure as a priest. A partially preserved inscription on one shoulder states that he prays to Ninshubur, the goddess associated with the planet Mercury Foundation Figure in the form of a peg surmounted by the bust of King Ur-Namma, Neo-Sumerian, Ur III period, reign of Ur-Namma,c. 2112–2094 BC

Foundation Figure in the form of a peg surmounted by the bust of King Ur-Namma, Neo-Sumerian, Ur III period, reign of Ur-Namma,c. 2112–2094 BC- A pair of Sumerian earrings, from the time of Shulgi, gold, Sulaymaniyah Museum (Iraq). The cuneiform inscriptions on this pair of earrings state that these earrings were a gift from king Shulgi. Cuneiform inscriptions on metal or on stone are very rare

Votive relief of Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, Early Dynastic III (2550–2500 BC), Louvre

Votive relief of Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, Early Dynastic III (2550–2500 BC), Louvre

Akkadian

Bronze head of King of Akkad, circa 2250 BC (Old Akkadian dynasty), copper alloy, 30 cm (11⁄4in), National Museum of Iraq(Baghdad). This finely worked sculpture produced using the lost-wax technique, had traditionally been identified with Sargon, founder of the Akkadian Empire, but is more likely to represent his grandson Naram-Sin. The eyes were gouged out in antiquity, apparently in an attempt to disfigure the image of the king. Naram-Sin was remembered in a later Mesopotamian legend as an impious ruler whose sacrilegious removal of treasures from the temple of Enlil at Nippur doomed his kingdom

Bronze head of King of Akkad, circa 2250 BC (Old Akkadian dynasty), copper alloy, 30 cm (11⁄4in), National Museum of Iraq(Baghdad). This finely worked sculpture produced using the lost-wax technique, had traditionally been identified with Sargon, founder of the Akkadian Empire, but is more likely to represent his grandson Naram-Sin. The eyes were gouged out in antiquity, apparently in an attempt to disfigure the image of the king. Naram-Sin was remembered in a later Mesopotamian legend as an impious ruler whose sacrilegious removal of treasures from the temple of Enlil at Nippur doomed his kingdom The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, Louvre

The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, Louvre- Seal impression

Impression of an Akkadian seal from circa 2350-2150 BCE

Impression of an Akkadian seal from circa 2350-2150 BCE

Babilonian

The reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate, Pergamon Museum, Berlin

The reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate, Pergamon Museum, Berlin Detail from a stele of the Code of Hammurabi

Detail from a stele of the Code of Hammurabi- Burney Relief represents a goddess, probably Ishtar, from Old Babylonian, around 1800 BCE, British Museum

Ceramic head, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ceramic head, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Assyrian

Gate of Nimrud with two lamassus, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Gate of Nimrud with two lamassus, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) "Winged genie", from Nimrud c. 870 BC, with inscription running across his midriff, British Museum

"Winged genie", from Nimrud c. 870 BC, with inscription running across his midriff, British Museum An ivory plaque which depicts a lion devouring a human, from Nimrud in the British Museum. The plaque still has much of its original gold leaf and paint

An ivory plaque which depicts a lion devouring a human, from Nimrud in the British Museum. The plaque still has much of its original gold leaf and paint Lamassu, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lamassu, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Eastern Mediterranean

Goddess who feeds goats

Goddess who feeds goats

Elamite

Silver cup with linear-Elamite inscription on it, from late 3rd millennium BC, in the National Museum of Iran

Silver cup with linear-Elamite inscription on it, from late 3rd millennium BC, in the National Museum of Iran Young woman spinning and servant holding a fan. Fragment of a relief known as "The spinner". Bitumen mastic, Neo-Elamite period (8th century BCE–middle of the 6th century BCE), found in Susa

Young woman spinning and servant holding a fan. Fragment of a relief known as "The spinner". Bitumen mastic, Neo-Elamite period (8th century BCE–middle of the 6th century BCE), found in Susa- Statue of Queen Napirasu, found at Susa, circa 1350 BC, made of bronze, 129 x 73 cm (50⁄4 x 28⁄4in), Louvre

Cylinder seal and modern impression- worshiper before a seated ruler or deity; seated female under a grape arbor, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cylinder seal and modern impression- worshiper before a seated ruler or deity; seated female under a grape arbor, Metropolitan Museum of Art Clay panels found at Susa by french archeologist Roland de Mecquenem, during his excavations of the Apadana tell, below the achaemenian level, Louvre

Clay panels found at Susa by french archeologist Roland de Mecquenem, during his excavations of the Apadana tell, below the achaemenian level, Louvre Guennol Lioness

Guennol Lioness Zoomorphic figurine from the neo-Elamite period, circa 1000-800 BCE, Indianapolis Museum of Art

Zoomorphic figurine from the neo-Elamite period, circa 1000-800 BCE, Indianapolis Museum of Art

Achaemenid

Achaemenid griffin capital at Persepolis

Achaemenid griffin capital at Persepolis One of a pair of armlets from the Oxus Treasure which has lost its inlays of precious stones or enamel

One of a pair of armlets from the Oxus Treasure which has lost its inlays of precious stones or enamel- Similar armlets in the "Apadana" reliefs at Persepolis, also bowls and amphorae with griffin handles are given as tribute

Bas-relief in Persepolis—a symbol in Zoroastrian for Nowruz— eternally fighting bull (personifying the moon), and a lion (personifying the Sun) representing the Spring

Bas-relief in Persepolis—a symbol in Zoroastrian for Nowruz— eternally fighting bull (personifying the moon), and a lion (personifying the Sun) representing the Spring

Egypt

In Egypt, one of the first great civilizations arose, which had elaborate and complex works of art which were produced by professional artists and craftspeople, who developed specialized skills. Egypt's art was religious and symbolic. Given that the culture had a highly centralized power structure and hierarchy, a great deal of art was created to honour the pharaoh, including great monuments. Egyptian culture emphasized the religious concept of immortality. Later Egyptian art includes Coptic and Byzantine art.

The architecture is characterized by monumental structures, built with large stone blocks, lintels, and solid columns. Funerary monuments included mastaba, tombs of rectangular form; pyramids, which included step pyramids (Saqqarah) or smooth-sided pyramids (Giza); and the hypogeum, underground tombs (Valley of the Kings). Other great buildings were the temple, which tended to be monumental complexes preceded by an avenue of sphinxes and obelisks. Temples used pylons and trapezoid walls with hypaethros and hypostyle halls and shrines. The temples of Karnak, Luxor, Philae and Edfu are good examples. Another type of temple is the rock temple, in the form of a hypogeum, found in Abu Simbel and Deir el-Bahari.

Painting of the Egyptian era used a juxtaposition of overlapping planes. The images were represented hierarchically, i.e., the Pharaoh is larger than the common subjects or enemies depicted at his side. Egyptians painted the outline of the head and limbs in profile, while the torso, hands, and eyes were painted from the front. Applied arts were developed in Egypt, in particular woodwork and metalwork. There are superb examples such as cedar furniture inlaid with ebony and ivory which can be seen in the tombs at the Egyptian Museum. Other examples include the pieces found in Tutankhamun's tomb, which are of great artistic quality.

Prehistoric Egypt (Naqada I & II; prior to 3100 BC)

Four naqada combs, decorated with a wildebeest, c. 3900–3500 B.C., ivory (elephant), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Four naqada combs, decorated with a wildebeest, c. 3900–3500 B.C., ivory (elephant), Metropolitan Museum of Art Two naqada I figurines

Two naqada I figurines Vessel painted with lanscape, circa 3400, pottery with red painted decoration, h. 30 x w. 31 cm (11 13/16 x 12 3/16} in), diam (of rim): 17 cm (6 11/16 in), diam (of opening): 14 cm (5⁄2 in), from Egypt, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City). Pottery vessels with bold, simple decoration of this type may not at first appear particularly pharaonic

Vessel painted with lanscape, circa 3400, pottery with red painted decoration, h. 30 x w. 31 cm (11 13/16 x 12 3/16} in), diam (of rim): 17 cm (6 11/16 in), diam (of opening): 14 cm (5⁄2 in), from Egypt, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City). Pottery vessels with bold, simple decoration of this type may not at first appear particularly pharaonic

Naqada III ("the protodynastic period"; approximately 3100–3000 BC)

Two faces of the Narmer Palette, Egyptian Museum (Cairo, Egypt)

Two faces of the Narmer Palette, Egyptian Museum (Cairo, Egypt)

Early Dynastic Period (First–Second Dynasties)

Old Kingdom (Third–Sixth Dynasties)

Middle Kingdom (Twelfth–Thirteenth Dynasties)

New Kingdom (Eighteenth–Twentieth Dynasties)

Great Sphinx of Giza

Great Sphinx of Giza This detail scene, from the Papyrus of Hunefer, the Book of the Dead, (c. 1275 BCE), shows the scribe Hunefer's heart being weighed on the scale of Maat against the feather of truth, by the jackal-headed Anubis

This detail scene, from the Papyrus of Hunefer, the Book of the Dead, (c. 1275 BCE), shows the scribe Hunefer's heart being weighed on the scale of Maat against the feather of truth, by the jackal-headed Anubis William the Faience Hippopotamus

William the Faience Hippopotamus Painting of a banquet (c. 1400 BC) with dancers and female musicians

Painting of a banquet (c. 1400 BC) with dancers and female musicians The gods Seth (left) and Horus(right) adoring Ramesses II in the small temple at Abu Simbel temples

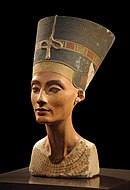

The gods Seth (left) and Horus(right) adoring Ramesses II in the small temple at Abu Simbel temples Bust of Nefertiti from the Ägyptisches Museum Berlincollection, presently in the Neues Museum.

Bust of Nefertiti from the Ägyptisches Museum Berlincollection, presently in the Neues Museum. A "house altar" depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti and three of their daughters; limestone; New Kingdom, Amarna period, 18th dynasty; c. 1350 BC - Collection: Ägyptisches Museum Berlin, Inv. 14145

A "house altar" depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti and three of their daughters; limestone; New Kingdom, Amarna period, 18th dynasty; c. 1350 BC - Collection: Ägyptisches Museum Berlin, Inv. 14145 Funerary mask of Tutankhamun, Egyptian Museum (Cairo, Egypt)

Funerary mask of Tutankhamun, Egyptian Museum (Cairo, Egypt) A jewelled falcon of Tutankhamun holding the ankh or sign for life in Ancient Egypt

A jewelled falcon of Tutankhamun holding the ankh or sign for life in Ancient Egypt A Wedjat/Udjat (Eye of Horus) pendant

A Wedjat/Udjat (Eye of Horus) pendant Solar scarab pendant from the tomb of Tutankhamun

Solar scarab pendant from the tomb of Tutankhamun A sarcophagus of Tutankhamun

A sarcophagus of Tutankhamun Fresco from Tutankhamun's tomb (KV62)

Fresco from Tutankhamun's tomb (KV62)

Late Period (Twenty-sixth–Thirty-first Dynasties)

Greek and Etruscan

Greek and Etruscan artists built on the artistic foundations of Egypt, further developing the arts of sculpture, painting, architecture, and ceramics. The body became represented in a more representational manner, and patronage of art thrived. Greek art started as smaller and simpler than Egyptian art, and the influence of Egyptian art on the Greeks started in the Cycladic islands between 3300–3200 B.C.E. Cycladic statues were simple, lacking facial features except for the nose.

Greek art eventually included life-sized statues, such as Kouros figures. The standing Kouros of Attica is typical of early Greek sculpture and dates from 600 B.C.E. From this early stage, the art of Greece moved into the Archaic Period. Sculpture from this time period includes the characteristic Archaic smile. This distinctive smile may have conveyed that the subject of the sculpture had been alive or that the subject had been blessed by the gods and was well.

Cycladic

- Male harp player from Keros, Cycladic, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Group of three Cycladic figurines, early Spedos type, Keros-Syros culture (EC II)

Group of three Cycladic figurines, early Spedos type, Keros-Syros culture (EC II) Marble seated harp player, Cyclades (Greece), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Marble seated harp player, Cyclades (Greece), Metropolitan Museum of Art Marble female figure, Cyclades, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Marble female figure, Cyclades, Metropolitan Museum of Art- Cycladic sculptures in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens

This figurine from the National Archaeological Museum of Athensdepicts a standing a man playing an aulos or a double flute

This figurine from the National Archaeological Museum of Athensdepicts a standing a man playing an aulos or a double flute Female figurine made between 2700-2300 BCE, Louvre

Female figurine made between 2700-2300 BCE, Louvre Woman head made between 2700-2300 BCE, Louvre

Woman head made between 2700-2300 BCE, Louvre This monumental female is the largest known example of a folded-arm figurine (1.5 m. high) and, with other types represents earliest surviving monumental sculpture from Greece. Its size suggests it may have served as a cult figure

This monumental female is the largest known example of a folded-arm figurine (1.5 m. high) and, with other types represents earliest surviving monumental sculpture from Greece. Its size suggests it may have served as a cult figure Cycladic kernos with geometric patterns, Louvre

Cycladic kernos with geometric patterns, Louvre A "frying pan", named for their similarity to the modern frying pans, there being no evidence to suggest these vessels were used for cooking, in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens

A "frying pan", named for their similarity to the modern frying pans, there being no evidence to suggest these vessels were used for cooking, in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens Cycladic pyxis decorated with spirals, from Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Cycladic pyxis decorated with spirals, from Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Minoan

Palace of Knossos, near Heraklion(in Crete, Greece). A long time ago, it's walls were full of Minoian frescos, most well-known being the "Prince of the Lilies". On Crete, the earlier Bronze Age is characterized by the presence of monumental, court-centred complexes at sites such as Knossos, Malia, Phaistosand Petras

Palace of Knossos, near Heraklion(in Crete, Greece). A long time ago, it's walls were full of Minoian frescos, most well-known being the "Prince of the Lilies". On Crete, the earlier Bronze Age is characterized by the presence of monumental, court-centred complexes at sites such as Knossos, Malia, Phaistosand Petras- Known as the Prince of the Lilies(also as the Priest King), this painted stucco relief, as it appears today, is the result of heavy restoration undertaken in 1905 by Swiss artist Emile Gilliéron Jnr, at the request of Arthur Evans. Imagined as a monumental, long-haired male waring a kilt and codpiece, a crown f feathers and lilies and a lily necklace. It has been suggested that Gilliéron's version combines fragments from a number of different figures, and several alternative interpretations have been offered. From circa 1675-1460 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Fresco of the Ladies in Blue. A largely restored fragment from a fresco which adorned the large ante-chamber of the Throne Room in the eastern wing of the Palace of Knossos. Ladies of the court, dressed with great elegance according to the fashion of the day, engage in conversation. The restoration is based on similar scenes found elsewhere. From 1675-1460 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Fresco of the Ladies in Blue. A largely restored fragment from a fresco which adorned the large ante-chamber of the Throne Room in the eastern wing of the Palace of Knossos. Ladies of the court, dressed with great elegance according to the fashion of the day, engage in conversation. The restoration is based on similar scenes found elsewhere. From 1675-1460 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum Part of a five-panel composition, the iconic Bull-Leaping Frescodepicts an acrobat at the back of a charging bull. A second figure prepares to leap, while a third waits with arms outstretched. The event may have resembled the Course landaise of modern southwest France. Bulls feature centrally in Knossian iconography and may have acted as a symbol of Knossian power. The central court may have served as an arena for bull-sports, although it was barely large enough. From 1675-1460 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Part of a five-panel composition, the iconic Bull-Leaping Frescodepicts an acrobat at the back of a charging bull. A second figure prepares to leap, while a third waits with arms outstretched. The event may have resembled the Course landaise of modern southwest France. Bulls feature centrally in Knossian iconography and may have acted as a symbol of Knossian power. The central court may have served as an arena for bull-sports, although it was barely large enough. From 1675-1460 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum- A group of faience Minoan snake goddess figurines (like the ome from the picture) were found in fragments among a collection of objects at Knossos that appear to represent the paraphernalia of an Minoan religion reserved for the palatial elite. Wearing religious dress and an elaborate hat with a feline perched atop, the goddess has been reconstructed holding aloft a pair of snakes. The goddess may represent one incarnation of the 'Mistress of Animals' (Potnia) referred to in Linear B. The deity is normally associated with nature and fertility, although the snakes suggest a chthonic component. From circa 1460-1410 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum

This is the most impressive of a small number of bull rhyta known from the Aegean. The presence of this and other examples at Knossos reflect the prominence of the bull in the political propaganda of the palace. The face and ears are made of steatite, bordered with jasper, and the muzzle is inlaid with tridacna (clam shell) from the Red Sea. The horns have been restored in gilt wood. A small graffito on the back of the neck suggests that they may originally have been sawn, perhaps following a practice observed during bull sacrifice. From circa 1700-1460 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum

This is the most impressive of a small number of bull rhyta known from the Aegean. The presence of this and other examples at Knossos reflect the prominence of the bull in the political propaganda of the palace. The face and ears are made of steatite, bordered with jasper, and the muzzle is inlaid with tridacna (clam shell) from the Red Sea. The horns have been restored in gilt wood. A small graffito on the back of the neck suggests that they may originally have been sawn, perhaps following a practice observed during bull sacrifice. From circa 1700-1460 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum The famous Bee pendant from Malia incorporates a variety of complex gold-working techniques including repoussé, filigree and granulation, and offers some idea of the technical and artistic skill of goldsmiths working on Creteduring Protopalatial period. The pendant depicts opposing beessupporting a drop of honey (or perhaps a pollen ball) elaborated with pendant discs at the wings and strings, and a filigree care with a small gold sphere (of unknown meaning) above their heads. From circa 1700-1600 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum

The famous Bee pendant from Malia incorporates a variety of complex gold-working techniques including repoussé, filigree and granulation, and offers some idea of the technical and artistic skill of goldsmiths working on Creteduring Protopalatial period. The pendant depicts opposing beessupporting a drop of honey (or perhaps a pollen ball) elaborated with pendant discs at the wings and strings, and a filigree care with a small gold sphere (of unknown meaning) above their heads. From circa 1700-1600 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum Kamares-style jug in the Herakleion Archaeological Museum, from the Old palatial period (2100-1700 B.C.). Kamares ware takes its name from the Kamares cave on the southern slope of Mount Ida (from Crete), one of the most important Minoan rural sanctuaries and the site at which the style was first recognized in 1890. Kamares ware appeared on Crete as the palace centeres emerged, and it developed alongside them over the course of the Middle Bronze Age. From circa 1850-1675 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Kamares-style jug in the Herakleion Archaeological Museum, from the Old palatial period (2100-1700 B.C.). Kamares ware takes its name from the Kamares cave on the southern slope of Mount Ida (from Crete), one of the most important Minoan rural sanctuaries and the site at which the style was first recognized in 1890. Kamares ware appeared on Crete as the palace centeres emerged, and it developed alongside them over the course of the Middle Bronze Age. From circa 1850-1675 BCE, in Heraklion Archaeological Museum The cave of Arkalochori is located about 3 km. (1⁄4 miles) south of the Minoan palace at Galatas and has yielded the largest assemblage of votive material of any Minoan cave sanctuary on Crete. A collection of bronze objects weighing more than 18 Turkish okas (22.5 kg/50 lb) was reportedly retrieved from the cave by locals and sold as scrap before the first systematic excavation in 1912. Among the incredible array of votive objects recovered since are some thirty gold double axes, or labrys, a religious symbol in the same manner as the Christian cross. From circa 1700-1460 BCE, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

The cave of Arkalochori is located about 3 km. (1⁄4 miles) south of the Minoan palace at Galatas and has yielded the largest assemblage of votive material of any Minoan cave sanctuary on Crete. A collection of bronze objects weighing more than 18 Turkish okas (22.5 kg/50 lb) was reportedly retrieved from the cave by locals and sold as scrap before the first systematic excavation in 1912. Among the incredible array of votive objects recovered since are some thirty gold double axes, or labrys, a religious symbol in the same manner as the Christian cross. From circa 1700-1460 BCE, Heraklion Archaeological Museum- The enigmatic Phaistos Disc has no prallel. It is thought by some to be a religious text, but both the language and meaning of the disc remain unknown. Its two faces preserve a total of 241 symbols representing 45 different pictographic signs, running from the edge to the center within an incised spiral band. Further incisions define individual groups of signs, perhaps representing single words. Incredibly, these signs were impressed usingindividual metal stamps, as in modern typography. Such stamps would probably have been used repeatedly, raising the possibility that other discs remain to be discovered. From circa 1700-1675 BCE, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

The large female figurines representing the Minoan goddesscome chiefly from the sanctuaries at Gazi, Gortys, Prinias, Knossosand Gournia. The largest and most typical group is that from Cazi (one of these is in the picture). The figurines, which are larger than any previously produced on Minoan Crete, are rendered in an extremely stylized manner in accordance with the artistic spirit of the period: the bodies are lifeless, the skirts simple cylinders, and the poses stereotyped. All the figures have raised hands; hence the name usually given to this type of figurine: "the goddess with raised hands". On the heads of the figures there are various symbols, such as horns of consecration, bird and the seeds of opium poppies. The figures with poppies are known as the "Poppy Goddesses", Heraklion Archaeological Museum

The large female figurines representing the Minoan goddesscome chiefly from the sanctuaries at Gazi, Gortys, Prinias, Knossosand Gournia. The largest and most typical group is that from Cazi (one of these is in the picture). The figurines, which are larger than any previously produced on Minoan Crete, are rendered in an extremely stylized manner in accordance with the artistic spirit of the period: the bodies are lifeless, the skirts simple cylinders, and the poses stereotyped. All the figures have raised hands; hence the name usually given to this type of figurine: "the goddess with raised hands". On the heads of the figures there are various symbols, such as horns of consecration, bird and the seeds of opium poppies. The figures with poppies are known as the "Poppy Goddesses", Heraklion Archaeological Museum This sarcophagus, known as the Hagia Triada sarcophagus, offers a unique narrative depiction of funerary ritual that incorporates both Minoan and Mycenaean elements, perhaps to convey a political message at a time when Crete may have fallen under Mycenaean control. Side A depicts a daytime scene with females pouring libations beneath a pair of double axes accompanied by a male lyre player, and a night scene showing men moving towards a figure who may represent the deceased. Side B depicts a pair of women sacrificing a bull, accompanied by a male flautist. On the terminal ends are female divinities an Mycenaean chariots drawn by griffin and others drawn by wild goats. From circa 1370-1315 BCE, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

This sarcophagus, known as the Hagia Triada sarcophagus, offers a unique narrative depiction of funerary ritual that incorporates both Minoan and Mycenaean elements, perhaps to convey a political message at a time when Crete may have fallen under Mycenaean control. Side A depicts a daytime scene with females pouring libations beneath a pair of double axes accompanied by a male lyre player, and a night scene showing men moving towards a figure who may represent the deceased. Side B depicts a pair of women sacrificing a bull, accompanied by a male flautist. On the terminal ends are female divinities an Mycenaean chariots drawn by griffin and others drawn by wild goats. From circa 1370-1315 BCE, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Mycenaean

Mycenaean palace amphora with an octopus on it, found in the Argolid, in the Archaeological Museum in Athens

Mycenaean palace amphora with an octopus on it, found in the Argolid, in the Archaeological Museum in Athens Lion Gate at Mycenae, the only known monumental sculpture of Bronze Age Greece

Lion Gate at Mycenae, the only known monumental sculpture of Bronze Age Greece Mask of Agamemnon, a gold funeral mask, dated 1550–1500 BC

Mask of Agamemnon, a gold funeral mask, dated 1550–1500 BC- The Dendra panoply or Dendra armour is an example of Mycenaean-era panoply (full-body armor) made of bronze plates uncovered in the village of Dendrain the Argolid (Greece), Archaeological Museum of Nafplion

Classical Greek

Statue of Zeus at Olympia in the sculptured antique art of Quatremère de Quincy (1815)

Statue of Zeus at Olympia in the sculptured antique art of Quatremère de Quincy (1815) Aphrodite of Knidos

Aphrodite of Knidos Heracles and Athena, black-figureside of a belly amphora by the Andokides Painter, from circa 520-510 BCE

Heracles and Athena, black-figureside of a belly amphora by the Andokides Painter, from circa 520-510 BCE Venus de Milo

Venus de Milo

Etruscan

- Etruscan head-shaped vase, Louvre

5th century BC fresco of dancers and musicians, Tomb of the Leopards, Monterozzi necropolis, Tarquinia, Italy

5th century BC fresco of dancers and musicians, Tomb of the Leopards, Monterozzi necropolis, Tarquinia, Italy- Sarcophagus of the Spouses, Cerveteri, 520 BCE, Louvre

Water jar with Herakles and the Hydra, c. 525 BC

Water jar with Herakles and the Hydra, c. 525 BC Etruscan dancer in the Tomb of the Augurs, Tarquinia, Italy

Etruscan dancer in the Tomb of the Augurs, Tarquinia, Italy- Etruscan sarcophagus, 3rd century BCE

Painted terracotta Sarcophagus of Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa, about 150-130 BCE

Painted terracotta Sarcophagus of Seianti Hanunia Tlesnasa, about 150-130 BCE

Dacian

Dacian art is the art associated with the peoples known as Dacians or North Thracians; The Dacians created an art style in which the influences of Scythians and the Greeks can be seen. They were highly skilled in gold and silver working and in pottery making. Pottery was white with red decorations in flolral, geometric, and stylized animal motifs. Similar decorations were worked in metal, especially the figure of a horse, which was common on Dacian coins.

The Golden Helmet of Coțofenești

The Golden Helmet of Coțofenești- Spiral motif with gold braceletfound in Romania (dated to Bronze IV = Hallstatt A)) repository Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Gold bracelet with horse heads from Vad-Făgăraș, Brașov Countyat Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Gold bracelet from Sarmizegetusa Regia – 1st century BC (NMIR Museum, Bucharest)

Gold bracelet from Sarmizegetusa Regia – 1st century BC (NMIR Museum, Bucharest) Dacian gold zoomorphic figurine, part of the Coțofenesti Treasure

Dacian gold zoomorphic figurine, part of the Coțofenesti Treasure

Pre-Roman Iberian

Pre-Roman Iberian art refers to the styles developed by the Iberians from the Bronze age up to the Roman conquest. For this reason it is sometimes described as "Iberian art".

Almost all extant works of Iberian sculpture visibly reflect Greek and Phoenician influences, and Assyrian, Hittite and Egyptian influences from which those derived; yet they have their own unique character. Within this complex stylistic heritage, individual works can be placed within a spectrum of influences- some of more obvious Phoenician derivation, and some so similar to Greek works that they could have been directly imported from that region. Overall the degree of influence is correlated to the work's region of origin, and hence they are classified into groups on that basis.

An eyed idol, Copper Age, named "Ídolo de Extremadura", National Archaeological Museum of Spain, Madrid

An eyed idol, Copper Age, named "Ídolo de Extremadura", National Archaeological Museum of Spain, Madrid The Lady of Elche, an iconic sculpture for the pre-Roman Iberian art

The Lady of Elche, an iconic sculpture for the pre-Roman Iberian art The Bicha of Balazote

The Bicha of Balazote The Lady of Baza

The Lady of Baza The Bulls of Guisando

The Bulls of Guisando

Hittite

Hittite art was produced by the Hittite civilization in ancient Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey, and also stretching into Syria during the second millennium BCE from the nineteenth century up until the twelfth century BCE. This period falls under the Anatolian Bronze Age. It is characterized by a long tradition of canonized images and motifs rearranged, while still being recognizable, by artists to convey meaning to a largely illiterate population.

Many of these recurring images revolve around the depiction of Hittite deities and ritual practices. There is also a prevalence of hunting scenes in Hittite relief and representational animal forms. Much of the art comes from settlements like Alaca Höyük, or the Hittite capital of Hattusa near modern-day Boğazkale. Scholars do have difficulty dating a large portion of Hittite art, citing the fact that there is a lack of inscription and much of the found material, especially from burial sites, was moved from their original locations and distributed among museums during the nineteenth century.

Sphinx Gate, Alaca Höyük, Turkey

Sphinx Gate, Alaca Höyük, Turkey- Baked clay Hittite rhyton, 19th century BCE

Ivory Hittite Sphinx, 18th century B.C.E.

Ivory Hittite Sphinx, 18th century B.C.E. Scene from Alaca Höyük Sphinx Gate

Scene from Alaca Höyük Sphinx Gate- The İvriz relief, king Warpalawas(right) before the god Tarhunzas

Vase A of the Hüseyindede vases

Vase A of the Hüseyindede vases Hittite Goddess And Child, "sun goddess of Arinna", 15th-13th Century BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Hittite Goddess And Child, "sun goddess of Arinna", 15th-13th Century BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art Luwian hieroglyphs surround a figure in royal dress. The inscription, repeated in cuneiform around the rim, gives the seal owner's name: the ruler Tarkasnawa of Mira. circa 1220 BC (Hittite Empire), made of silver, Walters Art Museum

Luwian hieroglyphs surround a figure in royal dress. The inscription, repeated in cuneiform around the rim, gives the seal owner's name: the ruler Tarkasnawa of Mira. circa 1220 BC (Hittite Empire), made of silver, Walters Art Museum

Bactrian

The Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex is the modern archaeological designation for a Bronze Age civilization of Central Asia, dated to c. 2300–1700 BC, located in present-day northern Afghanistan, eastern Turkmenistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, centred on the upper Amu Darya (Oxus River). Its sites were discovered and named by the Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi (1976).

BMAC materials have been found in the Indus Valley Civilisation, on the Iranian Plateau, and in the Persian Gulf. Finds within BMAC sites provide further evidence of trade and cultural contacts. They include an Elamite-type cylinder seal and a Harappan seal stamped with an elephant and Indus script found at Gonur-depe. The relationship between Altyn-Depe and the Indus Valley seems to have been particularly strong. Among the finds there were two Harappan seals and ivory objects. The Harappan settlement of Shortugai in Northern Afghanistan on the banks of the Amu Darya probably served as a trading station.

Seated Female Figure, chlorite and limestone, Bactria, 2500–1500 BC, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Dressed in a voluminous garment made of tufts of wool, this woman has a majestic bearing and an enigmatic smile

Seated Female Figure, chlorite and limestone, Bactria, 2500–1500 BC, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Dressed in a voluminous garment made of tufts of wool, this woman has a majestic bearing and an enigmatic smile Statuette of a kaunakes-wearing woman, known as "The Bactrian princess", between 3 millennium BCE and 2 millennium BCE, made of chlorite mineral group, limestone, height: 17.3 cm (6.8 in); width: 16.1 cm (6.3 in), Louvre

Statuette of a kaunakes-wearing woman, known as "The Bactrian princess", between 3 millennium BCE and 2 millennium BCE, made of chlorite mineral group, limestone, height: 17.3 cm (6.8 in); width: 16.1 cm (6.3 in), Louvre Female statuette bearing the kaunakes ("crinoline" dress). made of chlorite and limestone, beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, in Louvre

Female statuette bearing the kaunakes ("crinoline" dress). made of chlorite and limestone, beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, in Louvre Seated female statue made of steatite (the head) and chlorite (the dress) in circa late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Seated female statue made of steatite (the head) and chlorite (the dress) in circa late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art Shaft-hole Axe Head with Bird-Headed Demon, a Boar, and a Dragon figurine. From late 3rd - early 2nd millennium BC, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art(New York City)

Shaft-hole Axe Head with Bird-Headed Demon, a Boar, and a Dragon figurine. From late 3rd - early 2nd millennium BC, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art(New York City) Jar discovered in the Northern Afghanistan, circa 2700-2500 B.C., made of chlorite or steatite, in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Jar discovered in the Northern Afghanistan, circa 2700-2500 B.C., made of chlorite or steatite, in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Bactrian camel, made of copperalloy in circa late 3rd–early 2nd millennium B.C., Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bactrian camel, made of copperalloy in circa late 3rd–early 2nd millennium B.C., Metropolitan Museum of Art Bird-Headed Man with Snakes, bronze. Northern Afghanistan, 2000-1500 BC, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Bird-Headed Man with Snakes, bronze. Northern Afghanistan, 2000-1500 BC, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Celtic

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic languages.

The reverse side of a British bronze mirror, 50 BC - 50 AD, showing the spiral and trumpet decorative theme of the late "Insular" La Tènestyle

The reverse side of a British bronze mirror, 50 BC - 50 AD, showing the spiral and trumpet decorative theme of the late "Insular" La Tènestyle Carved stone ball from Towie in Aberdeenshire, dated from 3200–2500 BC

Carved stone ball from Towie in Aberdeenshire, dated from 3200–2500 BC Stone head from Mšecké Žehrovice, Czech Republic, wearing a torc, late La Tène culture

Stone head from Mšecké Žehrovice, Czech Republic, wearing a torc, late La Tène culture The Battersea Shield, England, 350-50 BC, for display rather than combat

The Battersea Shield, England, 350-50 BC, for display rather than combat The Wandsworth Shield-boss, in the "plastic" style

The Wandsworth Shield-boss, in the "plastic" style Pottery from Heuneburg, Germany

Pottery from Heuneburg, Germany Disc brooch, France, 4th century BC

Disc brooch, France, 4th century BC Parade Helmet, Agris, France, 350 BC, decorated in a mixture of Mediterranean styles

Parade Helmet, Agris, France, 350 BC, decorated in a mixture of Mediterranean styles The Strettweg Cult Wagon

The Strettweg Cult Wagon The Gundestrup cauldron

The Gundestrup cauldron

Rome

Roman art is sometimes viewed as derived from Greek precedents, but also has its own distinguishing features. Roman sculpture is often less idealized than the Greek precedents, being very realistic. Roman architecture often used concrete, and features such as the round arch and dome were invented.

Roman artwork was influenced by the nation-state's interaction with other people's, such as ancient Judea. A major monument is the Arch of Titus, which was erected by the Emperor Titus. Scenes of Romans looting the Jewish temple in Jerusalem are depicted in low-relief sculptures around the arch's perimeter.

Ancient Roman pottery was not a luxury product, but a vast production of "fine wares" in terra sigillata were decorated with reliefs that reflected the latest taste, and provided a large group in society with stylish objects at what was evidently an affordable price. Roman coins were an important means of propaganda, and have survived in enormous numbers.

Allegorical scene from the Augustan Ara Pacis, 13 BCE, a highpoint of the state Greco-Roman style

Allegorical scene from the Augustan Ara Pacis, 13 BCE, a highpoint of the state Greco-Roman style The "Capitoline Brutus", probably late 4th to early 3rd century BC, possibly 1st century BC.

The "Capitoline Brutus", probably late 4th to early 3rd century BC, possibly 1st century BC. A Roman naval bireme depicted in a relief from the Temple of Fortuna Primigenia in Praeneste(Palastrina), which was built c. 120 BC; exhibited in the Pius-Clementine Museum (Museo Pio-Clementino) in the Vatican Museums.

A Roman naval bireme depicted in a relief from the Temple of Fortuna Primigenia in Praeneste(Palastrina), which was built c. 120 BC; exhibited in the Pius-Clementine Museum (Museo Pio-Clementino) in the Vatican Museums. The Patrician Torlonia bust, believed to be of Cato the Elder. 1st century BC

The Patrician Torlonia bust, believed to be of Cato the Elder. 1st century BC Augustus of Prima Porta, statue of the emperor Augustus, 1st century CE. Vatican Museums

Augustus of Prima Porta, statue of the emperor Augustus, 1st century CE. Vatican Museums The cameo gem known as the "Great Cameo of France", c. 23 CE, with an allegory of Augustus and his family

The cameo gem known as the "Great Cameo of France", c. 23 CE, with an allegory of Augustus and his family Bust of Emperor Claudius, c. 50 CE, (reworked from a bust of emperor Caligula), It was found in the so-called Otricoli basilica in Lanuvium, Italy, Vatican Museums

Bust of Emperor Claudius, c. 50 CE, (reworked from a bust of emperor Caligula), It was found in the so-called Otricoli basilica in Lanuvium, Italy, Vatican Museums The so-called "Venus in a bikini", from the House of Julia Felix, Pompeii, Italy actually depicts her Greek conterpart Aphrodite as she is about to untie her sandal, with a small Eros squatting beneath her left arm

The so-called "Venus in a bikini", from the House of Julia Felix, Pompeii, Italy actually depicts her Greek conterpart Aphrodite as she is about to untie her sandal, with a small Eros squatting beneath her left arm- Tomb relief of the Decii, 98–117 CE

- Marcus Aurelius receiving the submission of vanquished foes from the Marcomannic Wars, a relief from his now destroyed triumphal arch in Rome, Capitoline Museums, 177-180 AD

Mosaic of Diana bathing, from As-Suwayda (Syria)

Mosaic of Diana bathing, from As-Suwayda (Syria)

is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License