History of art - Americas

Definition

The history of art in the Americas begins in pre-Columbian times with Indigenous cultures. Art historians have focused particularly closely on Mesoamerica during this early era, because a series of stratified cultures arose there that erected grand architecture and produced objects of fine workmanship that are comparable to the arts of Western Europe.

Preclassic

The art-making tradition of Mesoamerican people begins with the Olmec around 1400 BCE, during the Preclassic era. These people are best known for making colossal heads but also carved jade, erected monumental architecture, made small-scale sculpture, and designed mosaic floors. Two of the most well-studied sites artistically are San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán and La Venta. After the Olmec culture declined, the Maya civilization became prominent in the region. Sometimes a transitional Epi-Olmec period is described, which is a hybrid of Olmec and Maya. A particularly well-studied Epi-Olmec site is La Mojarra, which includes hieroglyphic carvings that have been partially deciphered.

Classic

By the late pre-Classic era, beginning around 400 BCE, the Olmec culture had declined but both Central Mexican and Maya peoples were thriving. Throughout much of the Classic period in Central Mexico, the city of Teotihuacan was thriving, as were Xochicalco and El Tajin. These sites boasted grand sculpture and architecture. Other Central Mexican peoples included the Mixtecs, the Zapotecs, and people in the Valley of Oaxaca. Maya art was at its height during the “Classic” period—a name that mirrors that of Classical European antiquity—and which began around 200 CE. Major Maya sites from this era include Copan, where numerous stelae were carved, and Quirigua where the largest stelae of Mesoamerica are located along with zoomorphic altars. A complex writing system was developed, and Maya illuminated manuscripts were produced in large numbers on paper made from tree bark. Many sites ”collapsed” around 1000 AD.

Postclassic

At the time of the Spanish conquest of Yucatán during the 16th and 17th centuries, the Maya were still powerful, but many communities were paying tribute to Aztec society. The latter culture was thriving, and it included arts such as sculpture, painting, and feather mosaics. Perhaps the most well-known work of Aztec art is the calendar stone, which became a national symbol of the state of Mexico. During the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, many of these artistic objects were sent to Europe, where they were placed in cabinets of curiosities, and later redistributed to Western art museums. The Aztec empire was based in the city of Tenochtitlan which was largely destroyed during the colonial era. What remains of it was buried beneath Mexico City. A few buildings, such as the foundation of the Templo Mayor have since been unearthed by archaeologists, but they are in poor condition.

Art in the Americas

Art in the Americas since the conquest is characterized by a mixture of indigenous and foreign traditions, including those of European, African, and Asian settlers. Numerous indigenous traditions thrived after the conquest. For example, the Plains Indians created quillwork, beadwork, winter counts, ledger art, and tipis in the pre-reservation era, and afterwards became assimilated into the world of Modern and Contemporary art through institutions such as the Santa Fe Indian School which encouraged students to develop a unique Native American style. Many paintings from that school, now called the Studio Style, were exhibited at the Philbrook Museum of Art during its Indian annual held from 1946 to 1979.

Central Mexico, Gulf Coast and Oaxaca

Art of Tlatilco culture

Female Figure, circa 1400-950 BC, Ceramic with slip, 9.53 x 3.81 cm (3⁄4 x 1⁄2 in), Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Female Figure, circa 1400-950 BC, Ceramic with slip, 9.53 x 3.81 cm (3⁄4 x 1⁄2 in), Los Angeles County Museum of Art Ceramics in form of a fish from Tlatilco, circa 1400-600 BC, National Museum of Anthropology(Mexico City)

Ceramics in form of a fish from Tlatilco, circa 1400-600 BC, National Museum of Anthropology(Mexico City)- Ceramic art recovered from Tlatilco, commonly known as the "Acrobat", c. 1300-800 BC

Two figurines, from the Manantial phase, 1000-800 BC

Two figurines, from the Manantial phase, 1000-800 BC

Olmec

Las Limas Monument 1, considered an important realisation of Olmec mythology. The youth holds a were-jaguar infant, while four iconic supernaturals are incised on the youth's shoulders and knees

Las Limas Monument 1, considered an important realisation of Olmec mythology. The youth holds a were-jaguar infant, while four iconic supernaturals are incised on the youth's shoulders and knees The Wrestler, an Olmec basalt statuette

The Wrestler, an Olmec basalt statuette An Olmec colossal head

An Olmec colossal head Hollow seated figure, circa 1200-900 BC (Early Pre-Classic), ceramic buffware with cream slip and red pigment, 30.2 × 23.2 × 16.5 cm (11.8 × 9.1 × 6.4 in), Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, USA)

Hollow seated figure, circa 1200-900 BC (Early Pre-Classic), ceramic buffware with cream slip and red pigment, 30.2 × 23.2 × 16.5 cm (11.8 × 9.1 × 6.4 in), Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, USA) Seated figure, 12th–9th century BC, cermaic with pigment, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York)

Seated figure, 12th–9th century BC, cermaic with pigment, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York) Infantile figure, circa 1200-900 BC (Early Pre-Classic), earthenware, 31.1 cm (12.2 in) high, Walters Art Museum

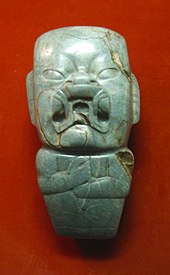

Infantile figure, circa 1200-900 BC (Early Pre-Classic), earthenware, 31.1 cm (12.2 in) high, Walters Art Museum Olmec jade mask, 10th–6th century B.C., in Metropolitan Museum of Art

Olmec jade mask, 10th–6th century B.C., in Metropolitan Museum of Art

Aztec

Mask of Quetzalcoatl or Tlaloc, circa 1400-1521, in the British Museum (London)

Mask of Quetzalcoatl or Tlaloc, circa 1400-1521, in the British Museum (London) Mask of Xiuhtecuhtli, circa 1400-1521, in the British Museum

Mask of Xiuhtecuhtli, circa 1400-1521, in the British Museum- Mask of Tezcatlipoca, circa 1400-1521, in the British Museum

Double-headed serpent

Double-headed serpent The 14th page of Codex Borbonicus

The 14th page of Codex Borbonicus The 15th page of Codex Borbonicus

The 15th page of Codex Borbonicus- Feather headdress of Moctezuma II, in the National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City)

Statue of Chalchiuhtlicue from National Museum of Anthropology

Statue of Chalchiuhtlicue from National Museum of Anthropology- The Aztec calendar stone, in the National Museum of Anthropology(Mexico City)

The Coatlicue statue, National Museum of Anthropology

The Coatlicue statue, National Museum of Anthropology- The Coyolxauhqui Stone,

Huaxtec, Toltec & others

Huaxtec statue of Tlazolteotl from Mexico, 900-1521 CE (British Museum, id:Am1989,Q.3 )

Huaxtec statue of Tlazolteotl from Mexico, 900-1521 CE (British Museum, id:Am1989,Q.3 ) Toltec warriors represented by the famous Atlantean figures in Tula, 900-1000 AD, made of basalt, 4.5–6 m (15–20 ft) high

Toltec warriors represented by the famous Atlantean figures in Tula, 900-1000 AD, made of basalt, 4.5–6 m (15–20 ft) high

Mayan

Mortuar mask of Pakal I, made of jade

Mortuar mask of Pakal I, made of jade Detail from the Skull Temple from Palenque, a Mayan site

Detail from the Skull Temple from Palenque, a Mayan site Codex style cylinder vessel, courtly ritual

Codex style cylinder vessel, courtly ritual Classic period sculpture showing sajal Aj Chak Maax presenting captives before ruler Itzamnaaj B'alam III of Yaxchilan

Classic period sculpture showing sajal Aj Chak Maax presenting captives before ruler Itzamnaaj B'alam III of Yaxchilan Page 9 of the Dresden Codex (from the 1880 Förstemann edition)

Page 9 of the Dresden Codex (from the 1880 Förstemann edition) El Castillo (pyramid of Kukulcán) in Chichén Itzá

El Castillo (pyramid of Kukulcán) in Chichén Itzá Jade plaque of a Maya king. Classic Period. Found at Teotihuacan, now in the British Museum

Jade plaque of a Maya king. Classic Period. Found at Teotihuacan, now in the British Museum Stucco portrait of king Pakal, from Palenque

Stucco portrait of king Pakal, from Palenque- Quetzalcoatl as a beraded serpent, circa 750 AD in Building A of Cacaxtla (Tlaxcala, Mexico). The ruins of Cacaxtla are stuated approximately 25 km south-west of the city of Tlaxacala (in federal state of Tlaxcala). In excavations conduced in the 1970s, archeologists descovered large wall paintings with Central American iconography and symbolism which were in the Maya style. The painting at the enterance of Building A portrays a well-dressed man with black body paint and a feathered serpent on his back. He is the wing god Quetzalcoatl in the form of a bearded green feathered serpent. The identity of the man cannot be deduced from the context

Maya glyphs in stucco at the Museo de sitio in Palenque (Mexico)

Maya glyphs in stucco at the Museo de sitio in Palenque (Mexico) Eccentric flint, circa 600-900 AD

Eccentric flint, circa 600-900 AD A Chac-Mool statue from National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City, Mexico)

A Chac-Mool statue from National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City, Mexico)

Costa Rica and Panama

Long considered a backwater of culture and aesthetic expression, Central America's dynamic societies are now recognized as robust and innovative contribuitors to the arts of ancient Americas. The people of pre-Columbian Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama developed their own distinctive styles in spite of the region being a crossroads for millennia. Its peoples were not subsumed by outside influences but instead created, adopted and adapted al manner of ideas and technologies to suit their needs and temperaments. The region's isiosyncratic cultural traditions, religious beliefs and sociopolitical systems are reflected in unique artworks. A fundamental spiritual tenet was shamanism, the central principle of which decreedthat in a trance state, transformed into one's spirit companion form, a person could enter the supranatural realm and garner special power to affect worldly affairs. Central American artists devised ingenious ways to portray this transformation by merging into one figure human and animal characteristics; the jaguar, serpent and avian raport (falcon, eagle or vulture) were the main spirit forms.

Pedestalled plate, circa 7th-9th century AD, earthenware with slip, diameter: 26 cm (10⁄4 in), Musée du quai Branly. The serpent was a popular theme for pottery and gold adornments in pre-Columbian Panama. The dynamism of its portrayal and later ethno-historical datasuggest a symbolic association of the snake with concepts of universal life force. Serpent portrayals often combine different animal elements, such as the legs of a crocodile, seen here, which allude to the supranatural nature of the image

Pedestalled plate, circa 7th-9th century AD, earthenware with slip, diameter: 26 cm (10⁄4 in), Musée du quai Branly. The serpent was a popular theme for pottery and gold adornments in pre-Columbian Panama. The dynamism of its portrayal and later ethno-historical datasuggest a symbolic association of the snake with concepts of universal life force. Serpent portrayals often combine different animal elements, such as the legs of a crocodile, seen here, which allude to the supranatural nature of the image Bird Pendant from Costa Rica, circa 1st–5th century AD, made of jadeite, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Bird Pendant from Costa Rica, circa 1st–5th century AD, made of jadeite, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Pectoral from Panama, made of gold, circa 400-900 AD, Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, USA)

Pectoral from Panama, made of gold, circa 400-900 AD, Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, USA) Amphibian pendant, circa 9th-16th century AD, made of gold, 8.2 cm (3.2 in), Walters Art Museum(Baltimore, USA). This gold pendant combines the characteristics of a frog, an iguana, a crocodile and a shark. The motif seen coming from the creature's mouth is a double-headed crocodile. This stylized motif is seen everywhere in Pre-Conquest Panamanian art. Smaller crocodile heads sprout from the creature's "shoulders" to support the double headed crocodiles coming out of the animal's mouth. The head appears to be that of a frog, with large, round eyes that bulge out

Amphibian pendant, circa 9th-16th century AD, made of gold, 8.2 cm (3.2 in), Walters Art Museum(Baltimore, USA). This gold pendant combines the characteristics of a frog, an iguana, a crocodile and a shark. The motif seen coming from the creature's mouth is a double-headed crocodile. This stylized motif is seen everywhere in Pre-Conquest Panamanian art. Smaller crocodile heads sprout from the creature's "shoulders" to support the double headed crocodiles coming out of the animal's mouth. The head appears to be that of a frog, with large, round eyes that bulge out

Colombia

Zoomorphico-antropomorphic figures from San Agustín Archaeological Park

Zoomorphico-antropomorphic figures from San Agustín Archaeological Park Figure of a deity from San Agustín Archaeological Park

Figure of a deity from San Agustín Archaeological Park Figure of a deity from San Agustín Archaeological Park

Figure of a deity from San Agustín Archaeological Park Muisca raft

Muisca raft Two sitting Quimbayan statuettes, one (the right one) of a cacique(chief, leader), both from Colombia

Two sitting Quimbayan statuettes, one (the right one) of a cacique(chief, leader), both from Colombia Lime container, 5th-9th century AD, made of gold, 23 cm (9 in) high, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Likely used by a member of the Quimbaya elite, this expertly fashioned and graceful container for powdered lime (poporo) characterizes an exceptional period of metallurgy in central Colombia. Lime, made from calcined seashells, was used when chewing coca leaves to release their stimulant quality. The fine condition of this outstanding poporo suggests that it was found in a tomb

Lime container, 5th-9th century AD, made of gold, 23 cm (9 in) high, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Likely used by a member of the Quimbaya elite, this expertly fashioned and graceful container for powdered lime (poporo) characterizes an exceptional period of metallurgy in central Colombia. Lime, made from calcined seashells, was used when chewing coca leaves to release their stimulant quality. The fine condition of this outstanding poporo suggests that it was found in a tomb- Gold figurine, 1st-4th century, from Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- This pendant, worn by a leader of the Tairona people (dominant in northern Colombia in the 15th & 16th centuries) as a symbol of earthly and spiritual power, portrays a human male transformed into a leaf-nosed bat-shamanic spirit being. He strikes a ritual stance with slightly bent knees, raised shoulders and flexed arms. Emerging from his gead are two avian forms, the spirals behind them symbolizing supranatural forces

Muisca tunjo on stool, from Metropolitan Museum of Art

Muisca tunjo on stool, from Metropolitan Museum of Art Nose Ornament made of gold alloy, in Walters Art Museum

Nose Ornament made of gold alloy, in Walters Art Museum- Muisca pectoral made of tumbaga, circa 600-1600 CE

Ceramic figurine with tumbaga nose-ring, made by the Quimbaya civilization in 1200-1500 CE

Ceramic figurine with tumbaga nose-ring, made by the Quimbaya civilization in 1200-1500 CE

Andean regions

Chavín

Chavin vassel that depicts a feline rendered in relatively high relief, alternating with a cactus form that may refer to the hallucinogenic San Pedro cactus

Chavin vassel that depicts a feline rendered in relatively high relief, alternating with a cactus form that may refer to the hallucinogenic San Pedro cactus

Moche

Killer Whale, made by the Nazca culture, pottery, Larco Museum(Lima, Perú)

Killer Whale, made by the Nazca culture, pottery, Larco Museum(Lima, Perú) Double-Spout, Bridge-Handle Vessel, in the Brooklyn Museum

Double-Spout, Bridge-Handle Vessel, in the Brooklyn Museum 1953 aerial photograph by Maria Reiche, one of the first archaeologists to study the Nazca lines

1953 aerial photograph by Maria Reiche, one of the first archaeologists to study the Nazca lines Ear ornaments made of gold, turquoise, sodalite, shell, bh the Moche culture, in the 3rd–7th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ear ornaments made of gold, turquoise, sodalite, shell, bh the Moche culture, in the 3rd–7th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art- A Moche portrait vessel, in the Art Institute of Chicago

Moche warrior pot from the British Museum (London)

Moche warrior pot from the British Museum (London)

Sican

Tomb of the Lord of Sipán

Tomb of the Lord of Sipán- Sican culture

Tiwanaku

Gate of the Sun, near Lake Titicaca, in Bolivia

Gate of the Sun, near Lake Titicaca, in Bolivia

Inca art

Golden Inca figure from Peru of a standing man

Golden Inca figure from Peru of a standing man Royal Inca tunic held at Dumbarton Oaks library (Washington D.C.). It was created between 1450 and 1540, made of wool and cotton. Dimensions: 90.2 x 77.15 cm.

Royal Inca tunic held at Dumbarton Oaks library (Washington D.C.). It was created between 1450 and 1540, made of wool and cotton. Dimensions: 90.2 x 77.15 cm.

Amazonia & the Caraibbes

Burial urn, Marajoara culture, American Museum of Natural History

Burial urn, Marajoara culture, American Museum of Natural History Large funerary vessel from Marajo island (Brazil), made in the Joanes style, from the Marajoara phase

Large funerary vessel from Marajo island (Brazil), made in the Joanes style, from the Marajoara phase Marajoara pottery

Marajoara pottery Marajoara bowl

Marajoara bowl

United States, Canada and Greenland

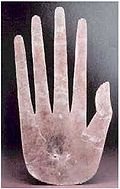

Carved mica hand, Hopewell Mounds, 100 BCE - 400 CE

Carved mica hand, Hopewell Mounds, 100 BCE - 400 CE Haida totem pole, Thunderbird Park, British Columbia

Haida totem pole, Thunderbird Park, British Columbia Seed jar by Hopi artist Nampeyo c. 1905

Seed jar by Hopi artist Nampeyo c. 1905

Inuit

Angakkuq sculpture, an Iunitartwork, by Pallaya Qiatsuq (Cape Dorset, Nunavut Territory, Canada)

Angakkuq sculpture, an Iunitartwork, by Pallaya Qiatsuq (Cape Dorset, Nunavut Territory, Canada) Rigure of a Tupilak from Greenland

Rigure of a Tupilak from Greenland Faces made of serpentine by Napatsi Ashoona (Cape Dorset, 1999)

Faces made of serpentine by Napatsi Ashoona (Cape Dorset, 1999)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License