Nitrogen

Definition

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | colorless gas, liquid or solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight (Ar, standard) | [14.00643, 14.00728] conventional: 14.007 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nitrogen in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 15 (pnictogens) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | reactive nonmetal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s 2p | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Electrons per shell | 2, 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | gas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 63.15 K (−210.00 °C, −346.00 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 77.355 K (−195.795 °C, −320.431 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at STP) | 1.2504 g/L at 0 °C, 1013 mbar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at b.p.) | 0.808 g/cm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 63.151 K, 12.52 kPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 126.192 K, 3.3958 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | (N2) 0.72 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporisation | (N2) 5.56 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | (N2) 29.124 J/(mol•K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapour pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, −1, −2, −3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 3.04 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionisation energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 71±1 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 155 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellanea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | 353 m/s (gas, at 27 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 25.83×10 W/(m•K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 17778-88-0 7727-37-9 (N2) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Daniel Rutherford (1772) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Named by | Jean-Antoine Chaptal(1790) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of nitrogen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nitrogen is a chemical element with symbol N and atomic number 7. It was first discovered and isolated by Scottish physician Daniel Rutherford in 1772. Although Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Henry Cavendish had independently done so at about the same time, Rutherford is generally accorded the credit because his work was published first. The name nitrogène was suggested by French chemist Jean-Antoine-Claude Chaptal in 1790, when it was found that nitrogen was present in nitric acid and nitrates. Antoine Lavoisier suggested instead the name azote, from the Greek άζωτικός "no life", as it is an asphyxiant gas; this name is instead used in many languages, such as French, Russian, and Turkish, and appears in the English names of some nitrogen compounds such as hydrazine, azides and azo compounds.

Nitrogen is the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. The name comes from the Greek πνίγειν "to choke", directly referencing nitrogen's asphyxiating properties. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at about seventh in total abundance in the Milky Way and the Solar System. At standard temperature and pressure, two atoms of the element bind to form dinitrogen, a colourless and odorless diatomic gas with the formula N2. Dinitrogen forms about 78% of Earth's atmosphere, making it the most abundant uncombined element. Nitrogen occurs in all organisms, primarily in amino acids (and thus proteins), in the nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) and in the energy transfer molecule adenosine triphosphate. The human body contains about 3% nitrogen by mass, the fourth most abundant element in the body after oxygen, carbon, and hydrogen. The nitrogen cycle describes movement of the element from the air, into the biosphere and organic compounds, then back into the atmosphere.

Many industrially important compounds, such as ammonia, nitric acid, organic nitrates (propellants and explosives), and cyanides, contain nitrogen. The extremely strong triple bond in elemental nitrogen (N≡N), the second strongest bond in any diatomic molecule after carbon monoxide (CO), dominates nitrogen chemistry. This causes difficulty for both organisms and industry in converting N2 into useful compounds, but at the same time means that burning, exploding, or decomposing nitrogen compounds to form nitrogen gas releases large amounts of often useful energy. Synthetically produced ammonia and nitrates are key industrial fertilisers, and fertiliser nitrates are key pollutants in the eutrophication of water systems.

Apart from its use in fertilisers and energy-stores, nitrogen is a constituent of organic compounds as diverse as Kevlar used in high-strength fabric and cyanoacrylate used in superglue. Nitrogen is a constituent of every major pharmacological drug class, including antibiotics. Many drugs are mimics or prodrugs of natural nitrogen-containing signal molecules: for example, the organic nitrates nitroglycerin and nitroprusside control blood pressure by metabolizing into nitric oxide. Many notable nitrogen-containing drugs, such as the natural caffeineand morphine or the synthetic amphetamines, act on receptors of animal neurotransmitters.

History

Nitrogen compounds have a very long history, ammonium chloride having been known to Herodotus. They were well known by the Middle Ages. Alchemists knew nitric acid as aqua fortis (strong water), as well as other nitrogen compounds such as ammonium salts and nitrate salts. The mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acids was known as aqua regia (royal water), celebrated for its ability to dissolve gold, the king of metals.

The discovery of nitrogen is attributed to the Scottish physician Daniel Rutherford in 1772, who called it noxious air. Though he did not recognise it as an entirely different chemical substance, he clearly distinguished it from Joseph Black's "fixed air", or carbon dioxide. The fact that there was a component of air that does not support combustion was clear to Rutherford, although he was not aware that it was an element. Nitrogen was also studied at about the same time by Carl Wilhelm Scheele, Henry Cavendish, and Joseph Priestley, who referred to it as burnt air or phlogisticated air. Nitrogen gas was inert enough that Antoine Lavoisier referred to it as "mephitic air" or azote, from the Greek word άζωτικός (azotikos), "no life". In an atmosphere of pure nitrogen, animals died and flames were extinguished. Though Lavoisier's name was not accepted in English, since it was pointed out that almost all gases (indeed, with the sole exception of oxygen) are mephitic, it is used in many languages (French, Italian, Portuguese, Polish, Russian, Albanian, Turkish, etc.; the German Stickstoff similarly refers to the same characteristic, viz. sticken "to choke or suffocate") and still remains in English in the common names of many nitrogen compounds, such as hydrazine and compounds of the azide ion. Finally, it led to the name "pnictogens" for the group headed by nitrogen, from the Greek πνίγειν "to choke".

The English word nitrogen (1794) entered the language from the French nitrogène, coined in 1790 by French chemist Jean-Antoine Chaptal(1756–1832), from the French nitre (potassium nitrate, also called saltpeter) and the French suffix -gène, "producing", from the Greek -γενής (-genes, "begotten"). Chaptal's meaning was that nitrogen is the essential part of nitric acid, which in turn was produced from niter. In earlier times, niter had been confused with Egyptian "natron" (sodium carbonate) – called νίτρον (nitron) in Greek – which, despite the name, contained no nitrate.

The earliest military, industrial, and agricultural applications of nitrogen compounds used saltpeter (sodium nitrate or potassium nitrate), most notably in gunpowder, and later as fertiliser. In 1910, Lord Rayleigh discovered that an electrical discharge in nitrogen gas produced "active nitrogen", a monatomic allotrope of nitrogen. The "whirling cloud of brilliant yellow light" produced by his apparatus reacted with mercury to produce explosive mercury nitride.

For a long time, sources of nitrogen compounds were limited. Natural sources originated either from biology or deposits of nitrates produced by atmospheric reactions. Nitrogen fixation by industrial processes like the Frank–Caro process (1895–1899) and Haber–Bosch process(1908–1913) eased this shortage of nitrogen compounds, to the extent that half of global food production (see Applications) now relies on synthetic nitrogen fertilisers. At the same time, use of the Ostwald process (1902) to produce nitrates from industrial nitrogen fixation allowed the large-scale industrial production of nitrates as feedstock in the manufacture of explosives in the World Wars of the 20th century.

Properties

Atomic

A nitrogen atom has seven electrons. In the ground state, they are arranged in the electron configuration 1s2

2s2

2p1

x2p1

y2p1

z. It therefore has five valence electrons in the 2s and 2p orbitals, three of which (the p-electrons) are unpaired. It has one of the highest electronegativities among the elements (3.04 on the Pauling scale), exceeded only by chlorine (3.16), oxygen (3.44), and fluorine(3.98). Following periodic trends, its single-bond covalent radius of 71 pm is smaller than those of boron (84 pm) and carbon(76 pm), while it is larger than those of oxygen (66 pm) and fluorine (57 pm). The nitride anion, N, is much larger at 146 pm, similar to that of the oxide (O: 140 pm) and fluoride (F: 133 pm) anions. The first three ionisation energies of nitrogen are 1.402, 2.856, and 4.577 MJ•mol, and the sum of the fourth and fifth is 16.920 MJ•mol. Due to these very high figures, nitrogen has no simple cationic chemistry.

2s2

2p1

x2p1

y2p1

z. It therefore has five valence electrons in the 2s and 2p orbitals, three of which (the p-electrons) are unpaired. It has one of the highest electronegativities among the elements (3.04 on the Pauling scale), exceeded only by chlorine (3.16), oxygen (3.44), and fluorine(3.98). Following periodic trends, its single-bond covalent radius of 71 pm is smaller than those of boron (84 pm) and carbon(76 pm), while it is larger than those of oxygen (66 pm) and fluorine (57 pm). The nitride anion, N, is much larger at 146 pm, similar to that of the oxide (O: 140 pm) and fluoride (F: 133 pm) anions. The first three ionisation energies of nitrogen are 1.402, 2.856, and 4.577 MJ•mol, and the sum of the fourth and fifth is 16.920 MJ•mol. Due to these very high figures, nitrogen has no simple cationic chemistry.

The lack of radial nodes in the 2p subshell is directly responsible for many of the anomalous properties of the first row of the p-block, especially in nitrogen, oxygen, and fluorine. The 2p subshell is very small and has a very similar radius to the 2s shell, facilitating orbital hybridisation. It also results in very large electrostatic forces of attraction between the nucleus and the valence electrons in the 2s and 2p shells, resulting in very high electronegativities. Hypervalency is almost unknown in the 2p elements for the same reason, because the high electronegativity makes it difficult for a small nitrogen atom to be a central atom in an electron-rich three-center four-electron bond since it would tend to attract the electrons strongly to itself. Thus, despite nitrogen's position at the head of group 15 in the periodic table, its chemistry shows huge differences from that of its heavier congeners phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, and bismuth.

Nitrogen may be usefully compared to its horizontal neighbours carbon and oxygen as well as its vertical neighbours in the pnictogen column (phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, and bismuth). Although each period 2 element from lithium to nitrogen shows some similarities to the period 3 element in the next group from magnesium to sulfur (known as the diagonal relationships), their degree drops off quite abruptly past the boron–silicon pair, so that the similarities of nitrogen to sulfur are mostly limited to sulfur nitride ring compounds when both elements are the only ones present. Nitrogen resembles oxygen far more than it does carbon with its high electronegativity and concomitant capability for hydrogen bonding and the ability to form coordination complexes by donating its lone pairs of electrons. It does not share carbon's proclivity for catenation, with the longest chain of nitrogen yet discovered being composed of only eight nitrogen atoms (PhN=N–N(Ph)–N=N–N(Ph)–N=NPh). One property nitrogen does share with both its horizontal neighbours is its preferentially forming multiple bonds, typically with carbon, nitrogen, or oxygen atoms, through pπ–pπ interactions; thus, for example, nitrogen occurs as diatomic molecules and thus has very much lower melting (−210 °C) and boiling points(−196 °C) than the rest of its group, as the N2 molecules are only held together by weak van der Waals interactions and there are very few electrons available to create significant instantaneous dipoles. This is not possible for its vertical neighbours; thus, the nitrogen oxides, nitrites, nitrates, nitro-, nitroso-, azo-, and diazo-compounds, azides, cyanates, thiocyanates, and imino-derivatives find no echo with phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, or bismuth. By the same token, however, the complexity of the phosphorus oxoacids finds no echo with nitrogen.

Isotopes

Nitrogen has two stable isotopes: N and N. The first is much more common, making up 99.634% of natural nitrogen, and the second (which is slightly heavier) makes up the remaining 0.366%. This leads to an atomic weight of around 14.007 u. Both of these stable isotopes are produced in the CNO cycle in stars, but N is more common as its neutron capture is the rate-limiting step. N is one of the five stable odd–odd nuclides (a nuclide having an odd number of protons and neutrons); the other four are H, Li, B, and Ta.

The relative abundance of N and N is practically constant in the atmosphere but can vary elsewhere, due to natural isotopic fractionation from biological redox reactions and the evaporation of natural ammonia or nitric acid. Biologically mediated reactions (e.g., assimilation, nitrification, and denitrification) strongly control nitrogen dynamics in the soil. These reactions typically result in N enrichment of the substrate and depletion of the product.

The heavy isotope N was first discovered by S. M. Naudé in 1929, soon after heavy isotopes of the neighbouring elements oxygen and carbon were discovered. It presents one of the lowest thermal neutron capture cross-sections of all isotopes. It is frequently used in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to determine the structures of nitrogen-containing molecules, due to its fractional nuclear spin of one-half, which offers advantages for NMR such as narrower line width. N, though also theoretically usable, has an integer nuclear spin of one and thus has a quadrupole moment that leads to wider and less useful spectra. N NMR nevertheless has complications not encountered in the more H and C NMR spectroscopy. The low natural abundance of N (0.36%) significantly reduces sensitivity, a problem which is only exacerbated by its low gyromagnetic ratio, (only 10.14% that of H). As a result, the signal-to-noise ratio for H is about 300 times as much as that for N at the same magnetic field strength. This may be somewhat alleviated by isotopic enrichment of N by chemical exchange or fractional distillation. N-enriched compounds have the advantage that under standard conditions, they do not undergo chemical exchange of their nitrogen atoms with atmospheric nitrogen, unlike compounds with labelled hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen isotopes that must be kept away from the atmosphere. The N:N ratio is commonly used in stable isotope analysis in the fields of geochemistry, hydrology, paleoclimatology and paleoceanography, where it is called δN.

Of the ten other isotopes produced synthetically, ranging from N to N, N has a half-life of ten minutes and the remaining isotopes have half-lives on the order of seconds (N and N) or even milliseconds. No other nitrogen isotopes are possible as they would fall outside the nuclear drip lines, leaking out a proton or neutron. Given the half-life difference, N is the most important nitrogen radioisotope, being relatively long-lived enough to use in positron emission tomography (PET), although its half-life is still short and thus it must be produced at the venue of the PET, for example in a cyclotron via proton bombardment of O producing N and an alpha particle.

The radioisotope N is the dominant radionuclide in the coolant of pressurised water reactors or boiling water reactors during normal operation, and thus it is a sensitive and immediate indicator of leaks from the primary coolant system to the secondary steam cycle, and is the primary means of detection for such leaks. It is produced from O (in water) via an (n,p) reactionin which the O atom captures a neutron and expels a proton. It has a short half-life of about 7.1 s, but during its decay back to O produces high-energy gamma radiation (5 to 7 MeV). Because of this, access to the primary coolant piping in a pressurised water reactor must be restricted during reactor power operation.

Chemistry and compounds

Allotropes

Atomic nitrogen, also known as active nitrogen, is highly reactive, being a triradical with three unpaired electrons. Free nitrogen atoms easily react with most elements to form nitrides, and even when two free nitrogen atoms collide to produce an excited N2 molecule, they may release so much energy on collision with even such stable molecules as carbon dioxideand water to cause homolytic fission into radicals such as CO and O or OH and H. Atomic nitrogen is prepared by passing an electric discharge through nitrogen gas at 0.1–2 mmHg, which produces atomic nitrogen along with a peach-yellow emission that fades slowly as an afterglow for several minutes even after the discharge terminates.

Given the great reactivity of atomic nitrogen, elemental nitrogen usually occurs as molecular N2, dinitrogen. This molecule is a colourless, odourless, and tasteless diamagnetic gas at standard conditions: it melts at −210 °C and boils at −196 °C.Dinitrogen is mostly unreactive at room temperature, but it will nevertheless react with lithium metal and some transition metal complexes. This is due to its bonding, which is unique among the diatomic elements at standard conditions in that it has an N≡N triple bond. Triple bonds have short bond lengths (in this case, 109.76 pm) and high dissociation energies (in this case, 945.41 kJ/mol), and are thus very strong, explaining dinitrogen's chemical inertness.

There are some theoretical indications that other nitrogen oligomers and polymers may be possible. If they could be synthesised, they may have potential applications as materials with a very high energy density, that could be used as powerful propellants or explosives. This is because they should all decompose to dinitrogen, whose N≡N triple bond (bond energy 946 kJ⋅mol) is much stronger than those of the N=N double bond (418 kJ⋅mol) or the N–N single bond (160 kJ⋅mol): indeed, the triple bond has more than thrice the energy of the single bond. (The opposite is true for the heavier pnictogens, which prefer polyatomic allotropes.) A great disadvantage is that most neutral polynitrogens are not expected to have a large barrier towards decomposition, and that the few exceptions would be even more challenging to synthesise than the long-sought but still unknown tetrahedrane. This stands in contrast to the well-characterised cationic and anionic polynitrogens azide (N−

3), pentazenium (N+

5), and pentazolide (cyclic aromatic N−

5). Under extremely high pressures (1.1 million atm) and high temperatures (2000 K), as produced in a diamond anvil cell, nitrogen polymerises into the single-bonded cubic gauche crystal structure. This structure is similar to that of diamond, and both have extremely strong covalent bonds, resulting in its nickname "nitrogen diamond".

3), pentazenium (N+

5), and pentazolide (cyclic aromatic N−

5). Under extremely high pressures (1.1 million atm) and high temperatures (2000 K), as produced in a diamond anvil cell, nitrogen polymerises into the single-bonded cubic gauche crystal structure. This structure is similar to that of diamond, and both have extremely strong covalent bonds, resulting in its nickname "nitrogen diamond".

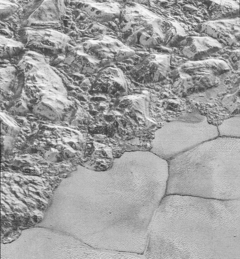

At atmospheric pressure, molecular nitrogen condenses (liquefies) at 77 K (−195.79 °C) and freezes at 63 K (−210.01 °C) into the beta hexagonal close-packed crystal allotropic form. Below 35.4 K (−237.6 °C) nitrogen assumes the cubic crystal allotropic form (called the alpha phase). Liquid nitrogen, a colourless fluid resembling water in appearance, but with 80.8% of the density (the density of liquid nitrogen at its boiling point is 0.808 g/mL), is a common cryogen. Solid nitrogen has many crystalline modifications. It forms a significant dynamic surface coverage on Pluto and outer moons of the Solar System such as Triton. Even at the low temperatures of solid nitrogen it is fairly volatile and can sublime to form an atmosphere, or condense back into nitrogen frost. It is very weak and flows in the form of glaciers and on Triton geysers of nitrogen gas come from the polar ice cap region.

Dinitrogen complexes

The first example of a dinitrogen complex to be discovered was [Ru(NH3)5(N2)] (see figure at right), and soon many other such complexes were discovered. These complexes, in which a nitrogen molecule donates at least one lone pair of electrons to a central metal cation, illustrate how N2might bind to the metal(s) in nitrogenase and the catalyst for the Haber process: these processes involving dinitrogen activation are vitally important in biology and in the production of fertilisers.

Dinitrogen is able to coordinate to metals in five different ways. The more well-characterised ways are the end-on M←N≡N (η) and M←N≡N→M (μ, bis-η), in which the lone pairs on the nitrogen atoms are donated to the metal cation. The less well-characterised ways involve dinitrogen donating electron pairs from the triple bond, either as a bridging ligand to two metal cations (μ, bis-η) or to just one (η). The fifth and unique method involves triple-coordination as a bridging ligand, donating all three electron pairs from the triple bond (μ3-N2). A few complexes feature multiple N2 ligands and some feature N2 bonded in multiple ways. Since N2 is isoelectronic with carbon monoxide (CO) and acetylene (C2H2), the bonding in dinitrogen complexes is closely allied to that in carbonyl compounds, although N2 is a weaker σ-donor and π-acceptor than CO. Theoretical studies show that σ donation is a more important factor allowing the formation of the M–N bond than π back-donation, which mostly only weakens the N–N bond, and end-on (η) donation is more readily accomplished than side-on (η) donation.

Today, dinitrogen complexes are known for almost all the transition metals, accounting for several hundred compounds. They are normally prepared by three methods:

- Replacing labile ligands such as H

2O, H, or CO directly by nitrogen: these are often reversible reactions that proceed at mild conditions. - Reducing metal complexes in the presence of a suitable coligand in excess under nitrogen gas. A common choice include replacing chloride ligands by dimethylphenylphosphine (PMe2Ph) to make up for the smaller number of nitrogen ligands attached than the original chlorine ligands.

- Converting a ligand with N–N bonds, such as hydrazine or azide, directly into a dinitrogen ligand.

Occasionally the N≡N bond may be formed directly within a metal complex, for example by directly reacting coordinated ammonia (NH3) with nitrous acid (HNO2), but this is not generally applicable. Most dinitrogen complexes have colours within the range white-yellow-orange-red-brown; a few exceptions are known, such as the blue [{Ti(η-C5H5)2}2-(N2)].

Nitrides, azides, and nitrido complexes

Nitrogen bonds to almost all the elements in the periodic table except the first three noble gases, helium, neon, and argon, and some of the very short-lived elements after bismuth, creating an immense variety of binary compounds with varying properties and applications. Many binary compounds are known: with the exception of the nitrogen hydrides, oxides, and fluorides, these are typically called nitrides. Many stoichiometric phases are usually present for most elements (e.g. MnN, Mn6N5, Mn3N2, Mn2N, Mn4N, and MnxN for 9.2 < x < 25.3). They may be classified as "salt-like" (mostly ionic), covalent, "diamond-like", and metallic (or interstitial), although this classification has limitations generally stemming from the continuity of bonding types instead of the discrete and separate types that it implies. They are normally prepared by directly reacting a metal with nitrogen or ammonia (sometimes after heating), or by thermal decomposition of metal amides:

- 3 Ca + N2 → Ca3N2

- 3 Mg + 2 NH3 → Mg3N2 + 3 H2 (at 900 °C)

- 3 Zn(NH2)2 → Zn3N2 + 4 NH3

Many variants on these processes are possible.The most ionic of these nitrides are those of the alkali metals and alkaline earth metals, Li3N (Na, K, Rb, and Cs do not form stable nitrides for steric reasons) and M3N2 (M = Be, Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba). These can formally be thought of as salts of the N anion, although charge separation is not actually complete even for these highly electropositive elements. However, the alkali metal azides NaN3 and KN3, featuring the linear N−

3 anion, are well-known, as are Sr(N3)2 and Ba(N3)2. Azides of the B-subgroup metals (those in groups 11 through 16) are much less ionic, have more complicated structures, and detonate readily when shocked.

3 anion, are well-known, as are Sr(N3)2 and Ba(N3)2. Azides of the B-subgroup metals (those in groups 11 through 16) are much less ionic, have more complicated structures, and detonate readily when shocked.

Many covalent binary nitrides are known. Examples include cyanogen ((CN)2), triphosphorus pentanitride (P3N5), disulfur dinitride (S2N2), and tetrasulfur tetranitride (S4N4). The essentially covalent silicon nitride (Si3N4) and germanium nitride(Ge3N4) are also known: silicon nitride in particular would make a promising ceramic if not for the difficulty of working with and sintering it. In particular, the group 13 nitrides, most of which are promising semiconductors, are isoelectronic with graphite, diamond, and silicon carbide and have similar structures: their bonding changes from covalent to partially ionic to metallic as the group is descended. In particular, since the B–N unit is isoelectronic to C–C, and carbon is essentially intermediate in size between boron and nitrogen, much of organic chemistry finds an echo in boron–nitrogen chemistry, such as in borazine ("inorganic benzene"). Nevertheless, the analogy is not exact due to the ease of nucleophilicattack at boron due to its deficiency in electrons, which is not possible in a wholly carbon-containing ring.

The largest category of nitrides are the interstitial nitrides of formulae MN, M2N, and M4N (although variable composition is perfectly possible), where the small nitrogen atoms are positioned in the gaps in a metallic cubic or hexagonal close-packed lattice. They are opaque, very hard, and chemically inert, melting only at very high temperatures (generally over 2500 °C). They have a metallic lustre and conduct electricity as do metals. They hydrolyse only very slowly to give ammonia or nitrogen.

The nitride anion (N) is the strongest π donor known amongst ligands (the second-strongest is O). Nitrido complexes are generally made by thermal decomposition of azides or by deprotonating ammonia, and they usually involve a terminal {≡N} group. The linear azide anion (N−

3), being isoelectronic with nitrous oxide, carbon dioxide, and cyanate, forms many coordination complexes. Further catenation is rare, although N4−

4 (isoelectronic with carbonate and nitrate) is known.

3), being isoelectronic with nitrous oxide, carbon dioxide, and cyanate, forms many coordination complexes. Further catenation is rare, although N4−

4 (isoelectronic with carbonate and nitrate) is known.

Hydrides

Industrially, ammonia (NH3) is the most important compound of nitrogen and is prepared in larger amounts than any other compound, because it contributes significantly to the nutritional needs of terrestrial organisms by serving as a precursor to food and fertilisers. It is a colourless alkaline gas with a characteristic pungent smell. The presence of hydrogen bonding has very significant effects on ammonia, conferring on it its high melting (−78 °C) and boiling (−33 °C) points. As a liquid, it is a very good solvent with a high heat of vaporisation (enabling it to be used in vacuum flasks), that also has a low viscosity and electrical conductivity and high dielectric constant, and is less dense than water. However, the hydrogen bonding in NH3 is weaker than that in H2O due to the lower electronegativity of nitrogen compared to oxygen and the presence of only one lone pair in NH3 rather than two in H2O. It is a weak base in aqueous solution (pK

b 4.74); its conjugate acid is ammonium, NH+

4. It can also act as an extremely weak acid, losing a proton to produce the amide anion, NH−

2. It thus undergoes self-dissociation, similar to water, to produce ammonium and amide. Ammonia burns in air or oxygen, though not readily, to produce nitrogen gas; it burns in fluorine with a greenish-yellow flame to give nitrogen trifluoride. Reactions with the other nonmetals are very complex and tend to lead to a mixture of products. Ammonia reacts on heating with metals to give nitrides.

b 4.74); its conjugate acid is ammonium, NH+

4. It can also act as an extremely weak acid, losing a proton to produce the amide anion, NH−

2. It thus undergoes self-dissociation, similar to water, to produce ammonium and amide. Ammonia burns in air or oxygen, though not readily, to produce nitrogen gas; it burns in fluorine with a greenish-yellow flame to give nitrogen trifluoride. Reactions with the other nonmetals are very complex and tend to lead to a mixture of products. Ammonia reacts on heating with metals to give nitrides.

Many other binary nitrogen hydrides are known, but the most important are hydrazine (N2H4) and hydrogen azide (HN3). Although it is not a nitrogen hydride, hydroxylamine (NH2OH) is similar in properties and structure to ammonia and hydrazine as well. Hydrazine is a fuming, colourless liquid that smells similarly to ammonia. Its physical properties are very similar to those of water (melting point 2.0 °C, boiling point 113.5 °C, density 1.00 g/cm). Despite it being an endothermic compound, it is kinetically stable. It burns quickly and completely in air very exothermically to give nitrogen and water vapour. It is a very useful and versatile reducing agent and is a weaker base than ammonia. It is also commonly used as a rocket fuel.

Hydrazine is generally made by reaction of ammonia with alkaline sodium hypochlorite in the presence of gelatin or glue:

- NH3 + OCl → NH2Cl + OH

- NH2Cl + NH3 → N2H+ 5 + Cl (slow)

- N2H+ 5 + OH → N2H4 + H2O (fast)

(The attacks by hydroxide and ammonia may be reversed, thus passing through the intermediate NHCl instead.) The reason for adding gelatin is that it removes metal ions such as Cu that catalyses the destruction of hydrazine by reaction with chloramine (NH2Cl) to produce ammonium chloride and nitrogen.

Hydrogen azide (HN3) was first produced in 1890 by the oxidation of aqueous hydrazine by nitrous acid. It is very explosive and even dilute solutions can be dangerous. It has a disagreeable and irritating smell and is a potentially lethal (but not cumulative) poison. It may be considered the conjugate acid of the azide anion, and is similarly analogous to the hydrohalic acids.

Halides and oxohalides

All four simple nitrogen trihalides are known. A few mixed halides and hydrohalides are known, but are mostly unstable and uninteresting: examples include NClF2, NCl2F, NBrF2, NF2H, NCl2H, and NClH2.

Five nitrogen fluorides are known. Nitrogen trifluoride (NF3, first prepared in 1928) is a colourless and odourless gas that is thermodynamically stable, and most readily produced by the electrolysis of molten ammonium fluoride dissolved in anhydrous hydrogen fluoride. Like carbon tetrafluoride, it is not at all reactive and is stable in water or dilute aqueous acids or alkalis. Only when heated does it act as a fluorinating agent, and it reacts with copper, arsenic, antimony, and bismuth on contact at high temperatures to give tetrafluorohydrazine (N2F4). The cations NF+

4 and N

2F+

3 are also known (the latter from reacting tetrafluorohydrazine with strong fluoride-acceptors such as arsenic pentafluoride), as is ONF3, which has aroused interest due to the short N–O distance implying partial double bonding and the highly polar and long N–F bond. Tetrafluorohydrazine, unlike hydrazine itself, can dissociate at room temperature and above to give the radical NF2•. Fluorine azide (FN3) is very explosive and thermally unstable. Dinitrogen difluoride(N2F2) exists as thermally interconvertible cis and trans isomers, and was first found as a product of the thermal decomposition of FN3.

4 and N

2F+

3 are also known (the latter from reacting tetrafluorohydrazine with strong fluoride-acceptors such as arsenic pentafluoride), as is ONF3, which has aroused interest due to the short N–O distance implying partial double bonding and the highly polar and long N–F bond. Tetrafluorohydrazine, unlike hydrazine itself, can dissociate at room temperature and above to give the radical NF2•. Fluorine azide (FN3) is very explosive and thermally unstable. Dinitrogen difluoride(N2F2) exists as thermally interconvertible cis and trans isomers, and was first found as a product of the thermal decomposition of FN3.

Nitrogen trichloride (NCl3) is a dense, volatile, and explosive liquid whose physical properties are similar to those of carbon tetrachloride, although one difference is that NCl3 is easily hydrolysed by water while CCl4 is not. It was first synthesised in 1811 by Pierre Louis Dulong, who lost three fingers and an eye to its explosive tendencies. As a dilute gas it is less dangerous and is thus used industrially to bleach and sterilise flour. Nitrogen tribromide (NBr3), first prepared in 1975, is a deep red, temperature-sensitive, volatile solid that is explosive even at −100 °C. Nitrogen triiodide (NI3) is still more unstable and was only prepared in 1990. Its adduct with ammonia, which was known earlier, is very shock-sensitive: it can be set off by the touch of a feather, shifting air currents, or even alpha particles. For this reason, small amounts of nitrogen triiodide are sometimes synthesised as a demonstration to high school chemistry students or as an act of "chemical magic". Chlorine azide (ClN3) and bromine azide (BrN3) are extremely sensitive and explosive.

Two series of nitrogen oxohalides are known: the nitrosyl halides (XNO) and the nitryl halides (XNO2). The first are very reactive gases that can be made by directly halogenating nitrous oxide. Nitrosyl fluoride (NOF) is colourless and a vigorous fluorinating agent. Nitrosyl chloride (NOCl) behaves in much the same way and has often been used as an ionising solvent. Nitrosyl bromide (NOBr) is red. The reactions of the nitryl halides are mostly similar: nitryl fluoride (FNO2) and nitryl chloride (ClNO2) are likewise reactive gases and vigorous halogenating agents.

Oxides

Nitrogen forms nine molecular oxides, some of which were the first gases to be identified: N2O (nitrous oxide), NO (nitric oxide), N2O3(dinitrogen trioxide), NO2 (nitrogen dioxide), N2O4 (dinitrogen tetroxide), N2O5 (dinitrogen pentoxide), N4O (nitrosylazide), and N(NO2)3 (trinitramide). All are thermally unstable towards decomposition to their elements. One other possible oxide that has not yet been synthesised is oxatetrazole (N4O), an aromatic ring.

Nitrous oxide (N2O), better known as laughing gas, is made by thermal decomposition of molten ammonium nitrate at 250 °C. This is a redox reaction and thus nitric oxide and nitrogen are also produced as byproducts. It is mostly used as a propellant and aerating agent for sprayed canned whipped cream, and was formerly commonly used as an anaesthetic. Despite appearances, it cannot be considered to be the anhydride of hyponitrous acid (H2N2O2) because that acid is not produced by the dissolution of nitrous oxide in water. It is rather unreactive (not reacting with the halogens, the alkali metals, or ozone at room temperature, although reactivity increases upon heating) and has the unsymmetrical structure N–N–O (N≡NO↔N=N=O): above 600 °C it dissociates by breaking the weaker N–O bond.

Nitric oxide (NO) is the simplest stable molecule with an odd number of electrons. In mammals, including humans, it is an important cellular signaling molecule involved in many physiological and pathological processes. It is formed by catalytic oxidation of ammonia. It is a colourless paramagnetic gas that, being thermodynamically unstable, decomposes to nitrogen and oxygen gas at 1100–1200 °C. Its bonding is similar to that in nitrogen, but one extra electron is added to a π* antibonding orbital and thus the bond order has been reduced to approximately 2.5; hence dimerisation to O=N–N=O is unfavourable except below the boiling point (where the cis isomer is more stable) because it does not actually increase the total bond order and because the unpaired electron is delocalised across the NO molecule, granting it stability. There is also evidence for the asymmetric red dimer O=N–O=N when nitric oxide is condensed with polar molecules. It reacts with oxygen to give brown nitrogen dioxide and with halogens to give nitrosyl halides. It also reacts with transition metal compounds to give nitrosyl complexes, most of which are deeply coloured.

Blue dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3) is only available as a solid because it rapidly dissociates above its melting point to give nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and dinitrogen tetroxide (N2O4). The latter two compounds are somewhat difficult to study individually because of the equilibrium between them. although sometimes dinitrogen tetroxide can react by heterolytic fission to nitrosonium and nitrate in a medium with high dielectric constant. Nitrogen dioxide is an acrid, corrosive brown gas. Both compounds may be easily prepared by decomposing a dry metal nitrate. Both react with water to form nitric acid. Dinitrogen tetroxide is very useful for the preparation of anhydrous metal nitrates and nitrato complexes, and it became the storable oxidiser of choice for many rockets in both the United States and USSR by the late 1950s. This is because it is a hypergolic propellant in combination with a hydrazine-based rocket fuel and can be easily stored since it is liquid at room temperature.

The thermally unstable and very reactive dinitrogen pentoxide (N2O5) is the anhydride of nitric acid, and can be made from it by dehydration with phosphorus pentoxide. It is of interest for the preparation of explosives. It is a deliquescent, colourless crystalline solid that is sensitive to light. In the solid state it is ionic with structure [NO2][NO3]; as a gas and in solution it is molecular O2N–O–NO2. Hydration to nitric acid comes readily, as does analogous reaction with hydrogen peroxide giving peroxonitric acid (HOONO2). It is a violent oxidising agent. Gaseous dinitrogen pentoxide decomposes as follows:

- N2O5 ⇌ NO2 + NO3 → NO2 + O2 + NO

- N2O5 + NO ⇌ 3 NO2

Oxoacids, oxoanions, and oxoacid salts

Many nitrogen oxoacids are known, though most of them are unstable as pure compounds and are known only as aqueous solution or as salts. Hyponitrous acid (H2N2O2) is a weak diprotic acid with the structure HON=NOH (pKa1 6.9, pKa2 11.6). Acidic solutions are quite stable but above pH 4 base-catalysed decomposition occurs via [HONNO] to nitrous oxide and the hydroxide anion. Hyponitrites (involving the N

2O2−

2 anion) are stable to reducing agents and more commonly act as reducing agents themselves. They are an intermediate step in the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite, which occurs in the nitrogen cycle. Hyponitrite can act as a bridging or chelating bidentate ligand.

2O2−

2 anion) are stable to reducing agents and more commonly act as reducing agents themselves. They are an intermediate step in the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite, which occurs in the nitrogen cycle. Hyponitrite can act as a bridging or chelating bidentate ligand.

Nitrous acid (HNO2) is not known as a pure compound, but is a common component in gaseous equilibria and is an important aqueous reagent: its aqueous solutions may be made from acidifying cool aqueous nitrite (NO−

2, bent) solutions, although already at room temperature disproportionation to nitrate and nitric oxide is significant. It is a weak acid with pKa 3.35 at 18 °C. They may be titrimetrically analysed by their oxidation to nitrate by permanganate. They are readily reduced to nitrous oxide and nitric oxide by sulfur dioxide, to hyponitrous acid with tin(II), and to ammonia with hydrogen sulfide. Salts of hydrazinium N

2H+

5 react with nitrous acid to produce azides which further react to give nitrous oxide and nitrogen. Sodium nitriteis mildly toxic in concentrations above 100 mg/kg, but small amounts are often used to cure meat and as a preservative to avoid bacterial spoilage. It is also used to synthesise hydroxylamine and to diazotise primary aromatic amines as follows:

2, bent) solutions, although already at room temperature disproportionation to nitrate and nitric oxide is significant. It is a weak acid with pKa 3.35 at 18 °C. They may be titrimetrically analysed by their oxidation to nitrate by permanganate. They are readily reduced to nitrous oxide and nitric oxide by sulfur dioxide, to hyponitrous acid with tin(II), and to ammonia with hydrogen sulfide. Salts of hydrazinium N

2H+

5 react with nitrous acid to produce azides which further react to give nitrous oxide and nitrogen. Sodium nitriteis mildly toxic in concentrations above 100 mg/kg, but small amounts are often used to cure meat and as a preservative to avoid bacterial spoilage. It is also used to synthesise hydroxylamine and to diazotise primary aromatic amines as follows:

- ArNH2 + HNO2 → [ArNN]Cl + 2 H2O

Nitrite is also a common ligand that can coordinate in five ways. The most common are nitro (bonded from the nitrogen) and nitrito (bonded from an oxygen). Nitro-nitrito isomerism is common, where the nitrito form is usually less stable.

Nitric acid (HNO3) is by far the most important and the most stable of the nitrogen oxoacids. It is one of the three most used acids (the other two being sulfuric acid and hydrochloric acid) and was first discovered by the alchemists in the 13th century. It is made by catalytic oxidation of ammonia to nitric oxide, which is oxidised to nitrogen dioxide, and then dissolved in water to give concentrated nitric acid. In the United States of America, over seven million tonnes of nitric acid are produced every year, most of which is used for nitrate production for fertilisers and explosives, among other uses. Anhydrous nitric acid may be made by distilling concentrated nitric acid with phosphorus pentoxide at low pressure in glass apparatus in the dark. It can only be made in the solid state, because upon melting it spontaneously decomposes to nitrogen dioxide, and liquid nitric acid undergoes self-ionisation to a larger extent than any other covalent liquid as follows:

- 2 HNO3 ⇌ H2NO+ 3 + NO− 3 ⇌ H2O + [NO2] + [NO3]

Two hydrates, HNO3•H2O and HNO3•3H2O, are known that can be crystallised. It is a strong acid and concentrated solutions are strong oxidising agents, though gold, platinum, rhodium, and iridium are immune to attack. A 3:1 mixture of concentrated hydrochloric acid and nitric acid, called aqua regia, is still stronger and successfully dissolves gold and platinum, because free chlorine and nitrosyl chloride are formed and chloride anions can form strong complexes. In concentrated sulfuric acid, nitric acid is protonated to form nitronium, which can act as an electrophile for aromatic nitration:

- HNO3 + 2 H2SO4 ⇌ NO+ 2 + H3O + 2 HSO− 4

The thermal stabilities of nitrates (involving the trigonal planar NO−

3 anion) depends on the basicity of the metal, and so do the products of decomposition (thermolysis), which can vary between the nitrite (for example, sodium), the oxide (potassium and lead), or even the metal itself (silver) depending on their relative stabilities. Nitrate is also a common ligand with many modes of coordination.

3 anion) depends on the basicity of the metal, and so do the products of decomposition (thermolysis), which can vary between the nitrite (for example, sodium), the oxide (potassium and lead), or even the metal itself (silver) depending on their relative stabilities. Nitrate is also a common ligand with many modes of coordination.

Finally, although orthonitric acid (H3NO4), which would be analogous to orthophosphoric acid, does not exist, the tetrahedral orthonitrate anion NO3−

4 is known in its sodium and potassium salts:

4 is known in its sodium and potassium salts:

These white crystalline salts are very sensitive to water vapour and carbon dioxide in the air:

- Na3NO4 + H2O + CO2 → NaNO3 + NaOH + NaHCO3

Despite its limited chemistry, the orthonitrate anion is interesting from a structural point of view due to its regular tetrahedral shape and the short N–O bond lengths, implying significant polar character to the bonding.

Organic nitrogen compounds

Nitrogen is one of the most important elements in organic chemistry. Many organic functional groups involve a carbon–nitrogen bond, such as amides (RCONR2), amines (R3N), imines(RC(=NR)R), imides (RCO)2NR, azides (RN3), azo compounds (RN2R), cyanates and isocyanates (ROCN or RCNO), nitrates (RONO2), nitriles and isonitriles (RCN or RNC), nitrites(RONO), nitro compounds (RNO2), nitroso compounds (RNO), oximes (RCR=NOH), and pyridine derivatives. C–N bonds are strongly polarised towards nitrogen. In these compounds, nitrogen is usually trivalent (though it can be tetravalent in quaternary ammonium salts, R4N), with a lone pair that can confer basicity on the compound by being coordinated to a proton. This may be offset by other factors: for example, amides are not basic because the lone pair is delocalised into a double bond (though they may act as acids at very low pH, being protonated at the oxygen), and pyrrole is not acidic because the lone pair is delocalised as part of an aromatic ring. The amount of nitrogen in a chemical substance can be determined by the Kjeldahl method. In particular, nitrogen is an essential component of nucleic acids, amino acids and thus proteins, and the energy-carrying molecule adenosine triphosphate and is thus vital to all life on Earth.

Occurrence

Nitrogen is the most common pure element in the earth, making up 78.1% of the entire volume of the atmosphere.Despite this, it is not very abundant in Earth's crust, making up only 19 parts per million of this, on par with niobium, gallium, and lithium. The only important nitrogen minerals are nitre (potassium nitrate, saltpetre) and sodanitre (sodium nitrate, Chilean saltpetre). However, these have not been an important source of nitrates since the 1920s, when the industrial synthesis of ammonia and nitric acid became common.

Nitrogen compounds constantly interchange between the atmosphere and living organisms. Nitrogen must first be processed, or "fixed", into a plant-usable form, usually ammonia. Some nitrogen fixation is done by lightning strikes producing the nitrogen oxides, but most is done by diazotrophic bacteria through enzymes known as nitrogenases (although today industrial nitrogen fixation to ammonia is also significant). When the ammonia is taken up by plants, it is used to synthesise proteins. These plants are then digested by animals who use the nitrogen compounds to synthesise their own proteins and excrete nitrogen–bearing waste. Finally, these organisms die and decompose, undergoing bacterial and environmental oxidation and denitrification, returning free dinitrogen to the atmosphere. Industrial nitrogen fixation by the Haber process is mostly used as fertiliser, although excess nitrogen–bearing waste, when leached, leads to eutrophication of freshwater and the creation of marine dead zones, as nitrogen-driven bacterial growth depletes water oxygen to the point that all higher organisms die. Furthermore, nitrous oxide, which is produced during denitrification, attacks the atmospheric ozone layer.

Many saltwater fish manufacture large amounts of trimethylamine oxide to protect them from the high osmotic effects of their environment; conversion of this compound to dimethylamine is responsible for the early odour in unfresh saltwater fish. In animals, free radical nitric oxide (derived from an amino acid), serves as an important regulatory molecule for circulation.

Nitric oxide's rapid reaction with water in animals results in production of its metabolite nitrite. Animal metabolism of nitrogen in proteins, in general, results in excretion of urea, while animal metabolism of nucleic acids results in excretion of urea and uric acid. The characteristic odour of animal flesh decay is caused by the creation of long-chain, nitrogen-containing amines, such as putrescine and cadaverine, which are breakdown products of the amino acids ornithine and lysine, respectively, in decaying proteins.

Production

Nitrogen gas is an industrial gas produced by the fractional distillation of liquid air, or by mechanical means using gaseous air (pressurised reverse osmosis membrane or pressure swing adsorption). Nitrogen gas generators using membranes or pressure swing adsorption (PSA) are typically more cost and energy efficient than bulk delivered nitrogen. Commercial nitrogen is often a byproduct of air-processing for industrial concentration of oxygen for steelmaking and other purposes. When supplied compressed in cylinders it is often called OFN (oxygen-free nitrogen). Commercial-grade nitrogen already contains at most 20 ppm oxygen, and specially purified grades containing at most 2 ppm oxygen and 10 ppm argon are also available.

In a chemical laboratory, it is prepared by treating an aqueous solution of ammonium chloride with sodium nitrite.

- NH4Cl + NaNO2 → N2 + NaCl + 2 H2O

Small amounts of the impurities NO and HNO3 are also formed in this reaction. The impurities can be removed by passing the gas through aqueous sulfuric acid containing potassium dichromate. Very pure nitrogen can be prepared by the thermal decomposition of barium azide or sodium azide.

- 2 NaN3 → 2 Na + 3 N2

Applications

Gas

The applications of nitrogen compounds are naturally extremely widely varied due to the huge size of this class: hence, only applications of pure nitrogen itself will be considered here. Two-thirds of nitrogen produced by industry is sold as the gas and the remaining one-third as the liquid. The gas is mostly used as an inert atmosphere whenever the oxygen in the air would pose a fire, explosion, or oxidising hazard. Some examples include:

- As a modified atmosphere, pure or mixed with carbon dioxide, to nitrogenate and preserve the freshness of packaged or bulk foods (by delaying rancidity and other forms of oxidative damage). Pure nitrogen as food additive is labeled in the European Union with the E number E941.

- In incandescent light bulbs as an inexpensive alternative to argon.

- In fire suppression systems for Information technology (IT) equipment.

- In the manufacture of stainless steel.

- In the case-hardening of steel by nitriding.

- In some aircraft fuel systems to reduce fire hazard (see inerting system).

- To inflate race car and aircraft tires, reducing the problems caused by moisture and oxygen in natural air.

Nitrogen is commonly used during sample preparation in chemical analysis. It is used to concentrate and reduce the volume of liquid samples. Directing a pressurised stream of nitrogen gas perpendicular to the surface of the liquid causes the solvent to evaporate while leaving the solute(s) and un-evaporated solvent behind.

Nitrogen can be used as a replacement, or in combination with, carbon dioxide to pressurise kegs of some beers, particularly stouts and British ales, due to the smaller bubbles it produces, which makes the dispensed beer smoother and headier. A pressure-sensitive nitrogen capsule known commonly as a "widget" allows nitrogen-charged beers to be packaged in cans and bottles. Nitrogen tanks are also replacing carbon dioxide as the main power source for paintball guns. Nitrogen must be kept at higher pressure than CO2, making N2 tanks heavier and more expensive. Nitrogen gas has become the inert gas of choice for inert gas asphyxiation, and is under consideration as a replacement for lethal injection in Oklahoma. Nitrogen gas, formed from the decomposition of sodium azide, is used for the inflation of airbags.

Liquid

Air balloon submerged in liquid nitrogen

Liquid nitrogen is a cryogenic liquid. When insulated in proper containers such as Dewar flasks, it can be transported without much evaporative loss.

Like dry ice, the main use of liquid nitrogen is as a refrigerant. Among other things, it is used in the cryopreservation of blood, reproductive cells (sperm and egg), and other biological samples and materials. It is used in the clinical setting in cryotherapy to remove cysts and warts on the skin. It is used in cold traps for certain laboratory equipment and to cool infrared detectors or X-ray detectors. It has also been used to cool central processing units and other devices in computers that are overclocked, and that produce more heat than during normal operation. Other uses include freeze-grinding and machining materials that are soft or rubbery at room temperature, shrink-fitting and assembling engineering components, and more generally to attain very low temperatures whenever necessary (around −200 °C). Because of its low cost, liquid nitrogen is also often used when such low temperatures are not strictly necessary, such as refrigeration of food, freeze-branding livestock, freezing pipes to halt flow when valves are not present, and consolidating unstable soil by freezing whenever excavation is going on underneath.

Safety

Gas

Although nitrogen is non-toxic, when released into an enclosed space it can displace oxygen, and therefore presents an asphyxiation hazard. This may happen with few warning symptoms, since the human carotid body is a relatively poor and slow low-oxygen (hypoxia) sensing system. An example occurred shortly before the launch of the first Space Shuttle mission in 1981, when two technicians died from asphyxiation after they walked into a space located in the Shuttle's Mobile Launcher Platform that was pressurised with pure nitrogen as a precaution against fire.

When inhaled at high partial pressures (more than about 4 bar, encountered at depths below about 30 m in scuba diving), nitrogen is an anesthetic agent, causing nitrogen narcosis, a temporary state of mental impairment similar to nitrous oxide intoxication.

Nitrogen dissolves in the blood and body fats. Rapid decompression (as when divers ascend too quickly or astronauts decompress too quickly from cabin pressure to spacesuit pressure) can lead to a potentially fatal condition called decompression sickness (formerly known as caisson sickness or the bends), when nitrogen bubbles form in the bloodstream, nerves, joints, and other sensitive or vital areas. Bubbles from other "inert" gases (gases other than carbon dioxide and oxygen) cause the same effects, so replacement of nitrogen in breathing gases may prevent nitrogen narcosis, but does not prevent decompression sickness.

Liquid

As a cryogenic liquid, liquid nitrogen can be dangerous by causing cold burns on contact, although the Leidenfrost effect provides protection for very short exposure (about one second).Ingestion of liquid nitrogen can cause severe internal damage. For example, in 2012, a young woman in England had to have her stomach removed after ingesting a cocktail made with liquid nitrogen.

Because the liquid-to-gas expansion ratio of nitrogen is 1:694 at 20 °C, a tremendous amount of force can be generated if liquid nitrogen is rapidly vaporised in an enclosed space. In an incident on January 12, 2006 at Texas A&M University, the pressure-relief devices of a tank of liquid nitrogen were malfunctioning and later sealed. As a result of the subsequent pressure buildup, the tank failed catastrophically. The force of the explosion was sufficient to propel the tank through the ceiling immediately above it, shatter a reinforced concrete beam immediately below it, and blow the walls of the laboratory 0.1–0.2 m off their foundations.

Liquid nitrogen readily evaporates to form gaseous nitrogen, and hence the precautions associated with gaseous nitrogen also apply to liquid nitrogen. For example, oxygen sensorsare sometimes used as a safety precaution when working with liquid nitrogen to alert workers of gas spills into a confined space.

Vessels containing liquid nitrogen can condense oxygen from air. The liquid in such a vessel becomes increasingly enriched in oxygen (boiling point −183 °C, higher than that of nitrogen) as the nitrogen evaporates, and can cause violent oxidation of organic material.

Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitrogen